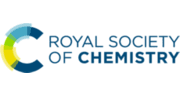

Hiroshi Yamagishi recently published his first independent research article with ChemComm. We wanted to celebrate this exciting milestone by finding out more about Hiroshi and his research. Check out his #ChemComm1st article: Facile light-initiated radical generation from 4-substituted pyridine under ambient conditions

We asked Hiroshi a few questions about his experience in the lab and working with ChemComm. Read more below.

What are the main areas of research in your lab and what motivated you to take this direction?

After receiving the PhD for the synthesis and fundamental structural investigation of supramolecular porous fibers and crystals, I was motivated to expand this research topic in regard to their functionality. Our group in University of Tsukuba is now focusing on the synthesis of molecular porous aggregates and investigating their host–guest chemistry and optical functions.

Can you set this article in a wider context?

The host porous crystal, Pyopen, is an attracting and counterintuitive compound. Although the constituent organic molecules are bound together via labile van der Waals-like forces (C–H···N bonds), the porous framework exhibits high thermal stability. Distinct from the conventional MOFs, COFs, or HOFs, the stability of Pyopen is based on the packing mode or the interdigitation of the molecules. We expect that the difference in the bonding regime should result in novel outcomes, and we are now investigating a series of chemical and physical characters of such molecular porous crystals sustained by van der Waals crystals. This article highlights one of the intriguing optical and chemical features of the van der Waals crystals.

What do you hope your lab can achieve in the coming year?

One of the fundamental yet challenging topics in the field of van der Waals porous crystal is to establish a molecular design strategy. Distinct from the MOFs, COFs, or HOFs, the prediction or designing of van der Waals porous crystal is yet to be established due to the extremely low bonding energy and the low directionality of van der Waals force. This topic is what I am now trying to overcome in the coming year.

Describe your journey to becoming independent researcher.

In the course of the PhD, I fortunately received an offer as a researcher from a chemical company and was really willing to join after I got the PhD. However, when I visited the UK as a guest researcher for half a year before joining the company, I occasionally met with a colleague in the University of Tsukuba there, who also visited UK for Sabbatical and proposed to me a position in University of Tsukuba. Through this experience, I understood from the heart the meaning of the sentence: “Nobody knows the future”.

What is the best piece of advice you have ever been given?

An advice from a colleague of mine was indeed impressive and encouraging to me. In the course of a discussion about a research result, he said “I hate the word ‘failure’. You did not fail, but revealed a novel fact that the reaction proceeded in a different way from what you expected”.

Why did you choose to publish in ChemComm?

ChemComm is a renowned journal that covers the diverse chemical sciences. Chemical Science is also attractive to me, but I prefer the communication format for publishing our results with urgency. Therefore, I chose ChemComm.

I am an Assistant Professor in Department of Materials Science, University of Tsukuba since 2018. I was educated at the University of Tokyo, gaining a PhD in 2018 for the development of intricate nanoporous organic and metal¬–organic architectures with distinct structural flexibility. I am currently focusing on optical resonators based on supramolecular aggregates with a view to realizing flexible lasers, displays, optical circuits and sensors. Compounds of interest covers organic linear and dendritic polymers, organic and metal–organic crystals, and organic liquid.

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Comm. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Comm. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at