Electro-oxidizing urea in water has the dual benefit of generating electricity and treating wastewater. In alkaline media, the sluggish kinetics of the urea oxidation reaction, CO(NH2)2 + 6OH– → N2↑ + CO2↑ + 5H2O + 6e–, due to its transfer of six electrons demand efficient catalysts to speed up this process.

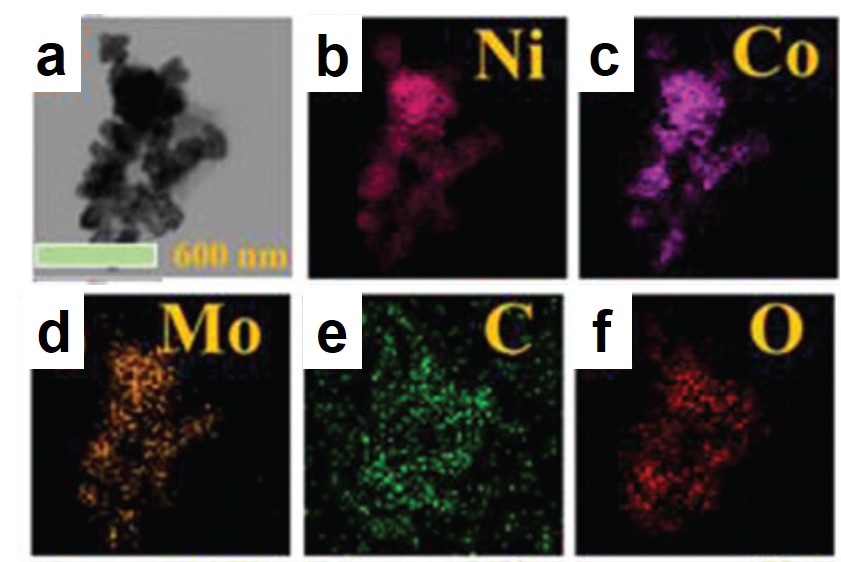

A research team led by Xiujuan Sun and Rui Ding, both at Xiangtan University, China, used a co-precipitation method to synthesize urea-oxidation catalysts. These catalysts comprised of graphene-anchored nanoparticles of metallic Ni, Co, and Mo, as well as their alloys and hydro/oxides (NCM/G) (Figure 1). NCM/G with the optimal composition displayed a mass activity of 140.9 mA cm-2 mgcat-1 and an onset potential of 1.32 V vs. RHE (current density = 10 mA/cm2). Their results are published in Chemical Communications (DOI: 10.1039/D0CC02132F).

Figure 1. Representative (a) transmission electron microscopy image and (b-f) elemental mappings of the synthesized catalyst.

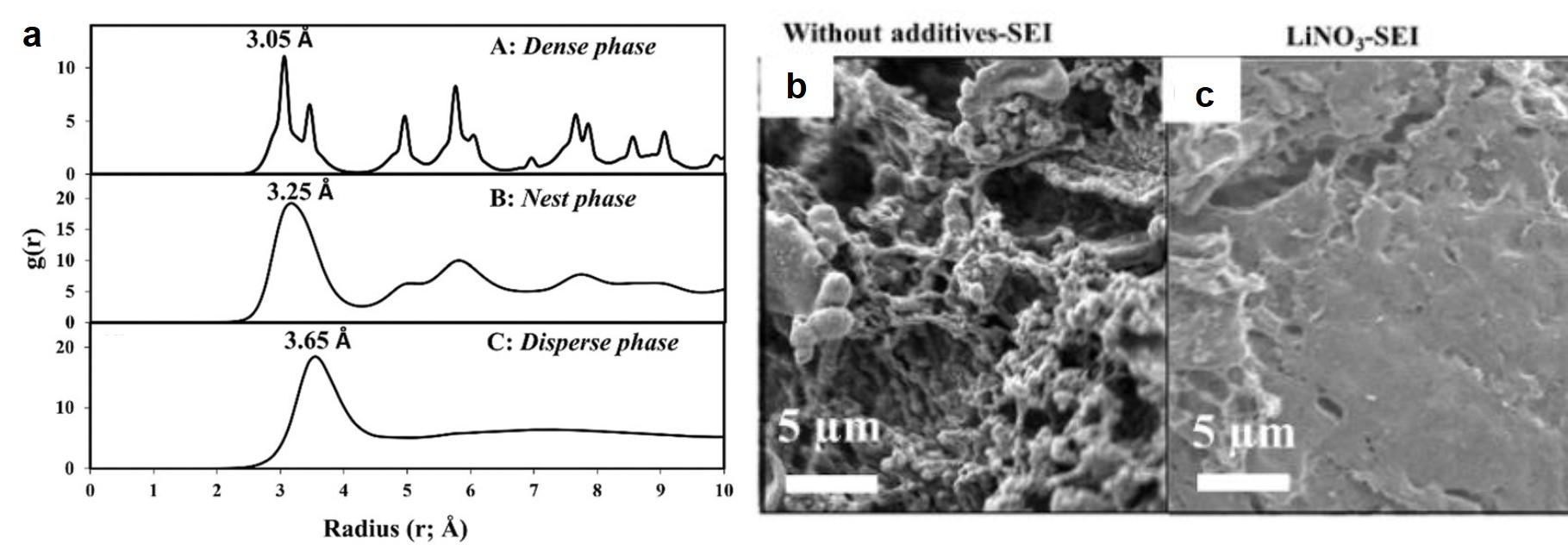

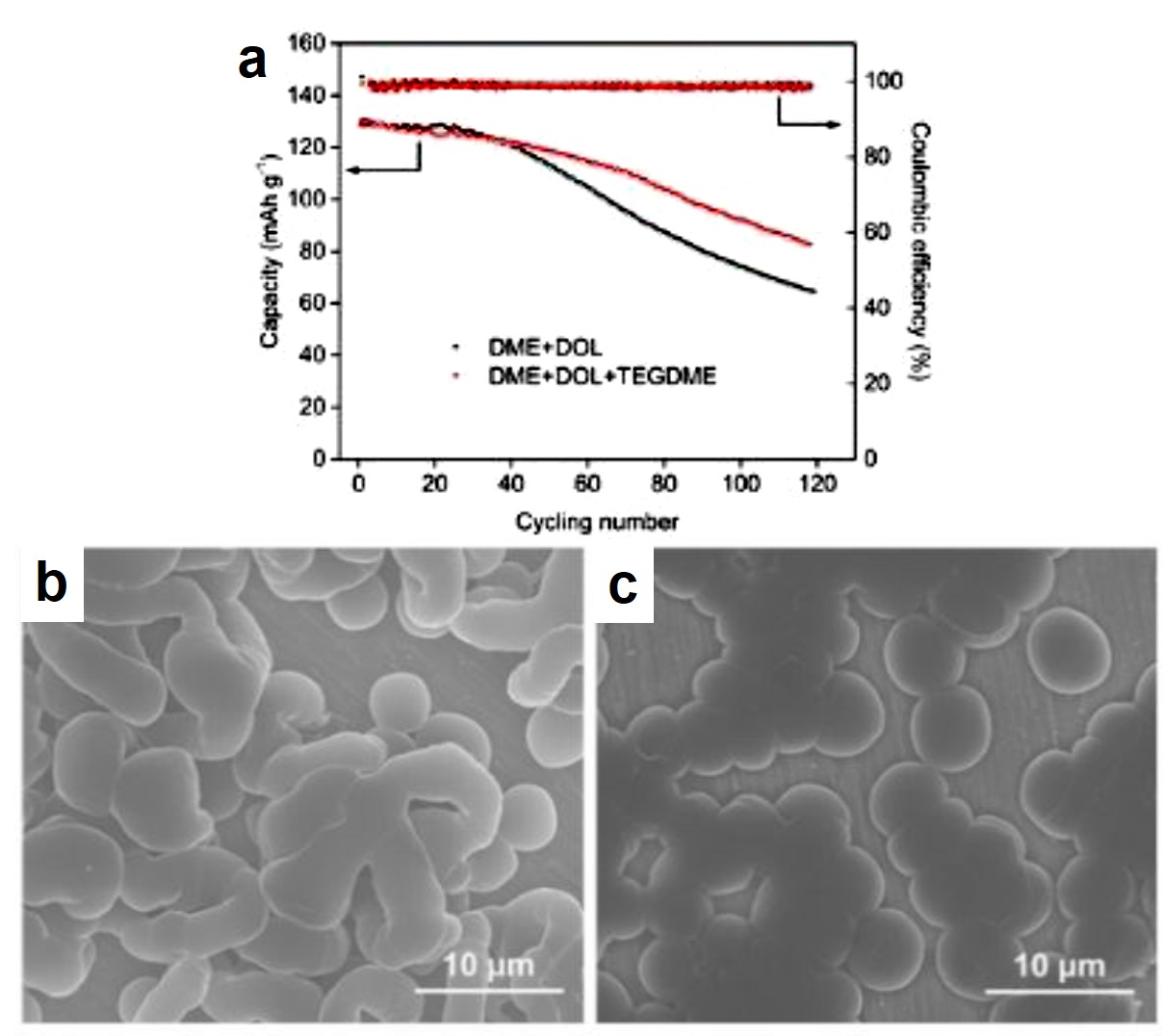

The catalysts exhibited different catalytic activities dependent on their chemical compositions, which were tunable by varying the moles of the Ni, Co, and Mo precursors. Cyclic voltammograms of various NCM/G all showed markedly increased current density at potentials beyond 0.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl in urea-containing aqueous solutions (Figure 2a), marking their catalytic activity for urea oxidation. Among all the tested catalysts, NCM/G with Ni:Co:Mo = 80:10:10 achieved the largest current density at 0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl, indicating its highest catalytic activity. Additionally, chronoamperometry demonstrated that increasing the Mo content was beneficial for maintaining catalyst stability, as the current density of NCM/G with the lowest amount of Mo (the black curve in Figure 2b) decayed the fastest. Combining the results of cyclic voltammetry and chronoamperometry, the authors deduced that the optimal molar ratio of Ni:Co:Mo was 80:10:10.

Figure 2. (a) Cyclic voltammograms (scan rate: 1 mV/s) and (b) chronoamperometry (potential: 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl) profiles of NCM/G with different Ni, Co, and Mo contents. Electrolyte: 1.0 M KOH + 0.33 M urea in water. The molar ratios of Ni:Co:Mo of NCM/G 90505, 811, and 71515 are 90:5:5. 80:10:10, and 70:15:15, respectively.

The optimization of the chemical composition demonstrated in this work can rationalize the development of high-performance, metallic electrocatalysts for urea oxidation.

For expanded understanding, please read:

Wei Shi, Xiujuan Sun, Rui Ding, Danfeng Ying, Yongfa Huang, Yuxi Huang, Caini Tan, Ziyang Jia, and Enhui Liu

Chem. Commun., 2020, DOI: 10.1039/D0CC02132F

Tianyu Liu acknowledges Zacary Croft at Virginia Tech, U.S., for his careful proofreading of this post.

About the blogger:

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Comm. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at http://liutianyuresearch.weebly.com/.

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Comm. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at http://liutianyuresearch.weebly.com/.