I know what you’re thinking: “Autumn is here! Who needs sunny weather and optimism? Sign me up for grey skies and vitamin D supplements!”. Oh you weren’t thinking that? Me neither. Well perhaps Halloween gives you more joy, along with the chance to see one of your colleagues dressed up like Freddy Mercury (‘Hg’ emblazoned on their chest, classic) at the departmental party?

In the spirit of Halloween, Simone Morra and Anca Pordea at the University of Nottingham have synthesized a mutant alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme turned Frankenstein catalyst, by replacing the zinc catalytic site with a covalently-bound rhodium(III) complex. The resulting mutant/transition-metal composite was used in combination with the wild-type enzyme to synthesize the chiral alcohol (S)-4-phenyl-2-butanol.

Like many hybrid systems, the purpose of combining enzymatic with transition metal catalysis is to take advantage of the benefits of each. Millions of years of evolution have produced enzymatic catalysts that function under mild conditions, in aqueous solvents, with impressive selectivity and high catalytic efficiency. But the narrow range of conditions that enzymes operate under can be disadvantageous in a synthetic setting. On the other hand, transition metal catalysts are versatile and can be easily customised, reacting with a liberty that would make the most promiscuous of enzymes blush.

Unfortunately, developing multi-component systems that utilise both transition metal and enzymatic catalysis is not as simple as combining them in a single mixture, as mutual deactivation often results. The authors found that encasing the transition metal complex in an enzyme provided a physical shield against inhibition, and preserved the activity of both the wild type enzyme and the rhodium(III) complex.

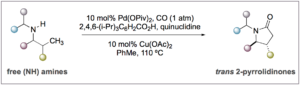

Synthesis of chiral alcohols via two interconnected cycles: the wild type enzyme (native ADH) reduces the ketone using NADPH as a reducing agent. NADPH is regenerated by the mutant enzyme containing a catalytically-active rhodium complex (chemically modified ADH) with formic acid as the terminal reductant.

Two interconnected catalytic cycles were responsible for synthesis of the chiral alcohol. In the first, the wild type enzyme effected reduction of 4-phenyl-2-butanol, a process that relies on the biological reductant nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). In the second cycle, NADPH was recycled using the composite rhodium(III) complex/mutant enzyme, with formic acid as the stoichiometric reductant. The rate of alcohol formation was slow (turnover frequency of 0.02 s-1) and the transition-metal catalysed process was deemed to be rate limiting (compare to turnover frequencies of 4.8 s-1 for enzymatic systems). However, near perfect enantioselectivity was obtained (>99% ee).

This research demonstrates one way that transition metal catalysts can augment the scope of co-factor-dependent enzymes. Furthermore, devising strategies to prepare metal-complex/enzyme bioconjugates might have value for small molecule synthesis due to the second coordination sphere that enzymes offer; an encased steric environment to guide the reaction outcome is a valuable approach to improving selectivity in catalytic reactions.

To find out more please read:

Biocatalyst-artifical metalloenzyme cascade based on alcohol dehydrogenase

Simone Morra, Anca Pordea.

Chem. Sci., 2018, 9, 7447-7454

DOI: 10.1039/c8sc02371a

About the author

Zoë Hearne is a PhD candidate in chemistry at McGill University in Montréal, Canada, under the supervision of Professor Chao-Jun Li. She hails from Canberra, Australia, where she completed her undergraduate degree. Her current research focuses on transition metal catalysis to effect novel transformations, and out of the lab she is an enthusiastic chemistry tutor and science communicator.

About the author

About the author