Our world runs on systems of ever-increasing complexity, be they natural or human created. Their behavior can generally be modeled and operates within a normal range… until it hits a tipping point at a border between two behavioral regimes. Once that threshold is reached the system acts in dramatically different, and often destructive, ways. However, there are often warning signs right around the tipping point that can serve to alert careful observers that the danger zone is near. By finding ways to identify and monitor this behavior either contingency plans can be put in place or the problem corrected before it becomes catastrophic. While much of this has been studied for large systems like the stock market or ecosystems, researchers recently applied this to chemical systems.

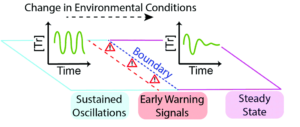

The utility of identifying early warning signals isn’t limited to preventing massive changes; it can also help bound regions of different functionality in chemical systems. To explore this, researchers used a trypsin oscillator system they previously developed that has two modes of flow (Figure 1), either sustained oscillations in trypsin concentration or dampened oscillations that eventually lead to a steady concentration of trypsin. By changing flow rate, temperature, or reagent concentration the researchers could tune the behavior of the system to test either active or passive monitoring schemes to find early warning signs. Since they knew what conditions produced each mode, they could operate the system right at the boundary and watch its behavior.

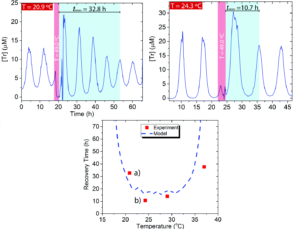

In the “active” experiments the researchers intervened in the system’s normal functioning and watched how its response, the “critical slow down phenomena,” changed as the conditions were brought closer to the boundary. In “passive” experiments, the researchers simply brought the system close to the boundary and monitored the shape of the oscillation waves focusing on their full-width half maxima (FWHM). In the series of active sensing experiments, the researchers waited to see how long it took the system to re-establish sustained oscillations after a change in temperature. They expected to see this recovery time increase as the system was brought closer to the edge, aka the “critical slow down phenomena.” In their experiment they elevated the temperature of the system to 49.0 oC and observed how long it took to recover to either 24.3 oC (well within the sustained regime) or 20.9 oC (near the behavioral boundary). They saw the expected dramatic increase in time to return to sustained oscillation, with the system recovering in 10.7 hrs at 24.3 oC, but taking three times as long, 32.8 hrs, when the final temperature was 20.9 oC (Figure 2). The experimental results were further validated by theoretical modeling, where experimentally challenging positions at the very edge of the boundary could be explored and showed the same general behavior.

Figure 2. Top: active monitoring experiments at two different temperatures showing the differences in time needed to recover sustained oscillations. Bottom: comparison of modeled and experimental recovery times.

The theoretical modeling was further used to create a map of passive monitoring space, looking at the variations in FWHM. They saw that as the system moves away from the center of the oscillation regime the FWHM increases as the peaks broaden. This becomes more pronounced as the conditions approach the behavioral boundary. This provides a baseline knowledge with multiple types of measurements to compare the stability of the simple system over a range of conditions. Additionally, this system and others like it can serve as the base for modeling more complex systems of which they are a part.

To find out more, please read:

Early warning signals in chemical reaction networks

Chem. Commun., 2020, Advance Article

Oliver R. Maguire, Albert S. Y. Wong, Jan Harm Westerdiep and Wilhelm T. S. Huck

About the blogger:

Dr. Beth Mundy recently received her PhD in chemistry from the Cossairt lab at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington. Her research focused on developing new and better ways to synthesize nanomaterials for energy applications. She is often spotted knitting in seminars or with her nose in a good book. You can find her on Twitter at @BethMundySci.

Dr. Beth Mundy recently received her PhD in chemistry from the Cossairt lab at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington. Her research focused on developing new and better ways to synthesize nanomaterials for energy applications. She is often spotted knitting in seminars or with her nose in a good book. You can find her on Twitter at @BethMundySci.

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from University of California, Santa Cruz in the United States. He is passionate about scientific communication to introduce cutting-edge research to both the general public and scientists with diverse research expertise. He is a blog writer for Chem. Commun. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from University of California, Santa Cruz in the United States. He is passionate about scientific communication to introduce cutting-edge research to both the general public and scientists with diverse research expertise. He is a blog writer for Chem. Commun. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at