Lithium–sulfur (Li–S) batteries are rechargeable batteries with elemental sulfur and metallic lithium as the cathode and anode, respectively. These batteries are promising electrochemical energy storage devices because their energy densities are three to five times higher than those of Li-ion batteries. Unfortunately, the practicality of Li–S batteries is hindered by their short lifetimes due to two processes that occur on the Li anode surface: the growth of Li dendrites and the irreversible polysulfide reduction. Adding LiNO3 into battery electrolytes has proven to be useful to prolong battery lifetimes, but the underlying mechanism is uncertain.

In Chemical Communications (doi: 10.1039/c9cc06504k), Sawangphruk and coworkers from Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology, Thailand have offered valuable insights to settle the dispute over the effects of LiNO3. The researchers performed theoretical reactive molecular dynamics simulations and elucidated two roles of LiNO3 in Li–S batteries.

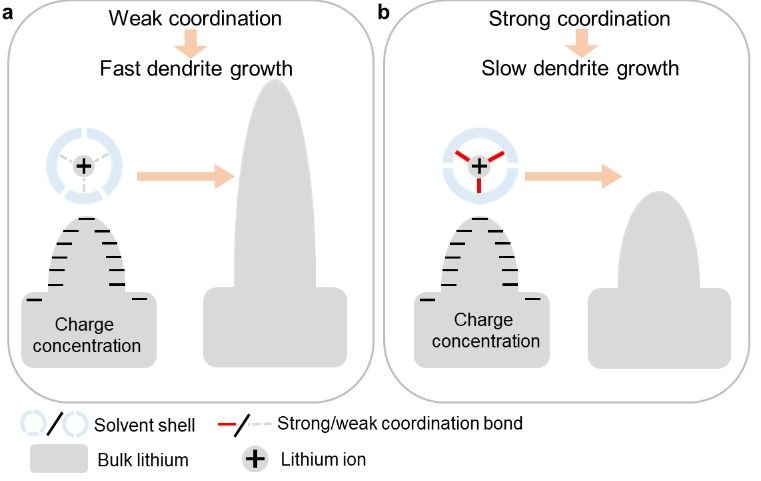

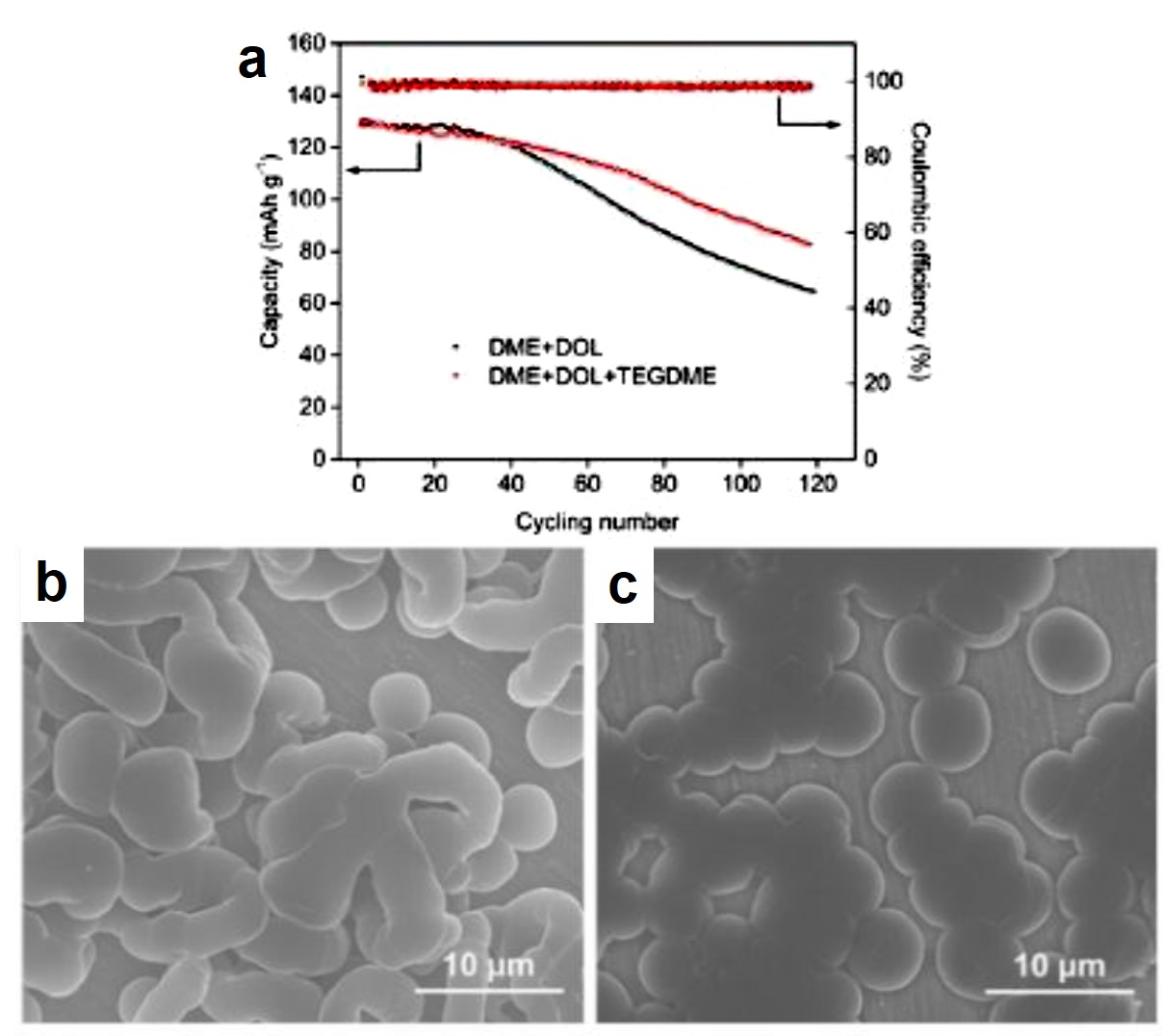

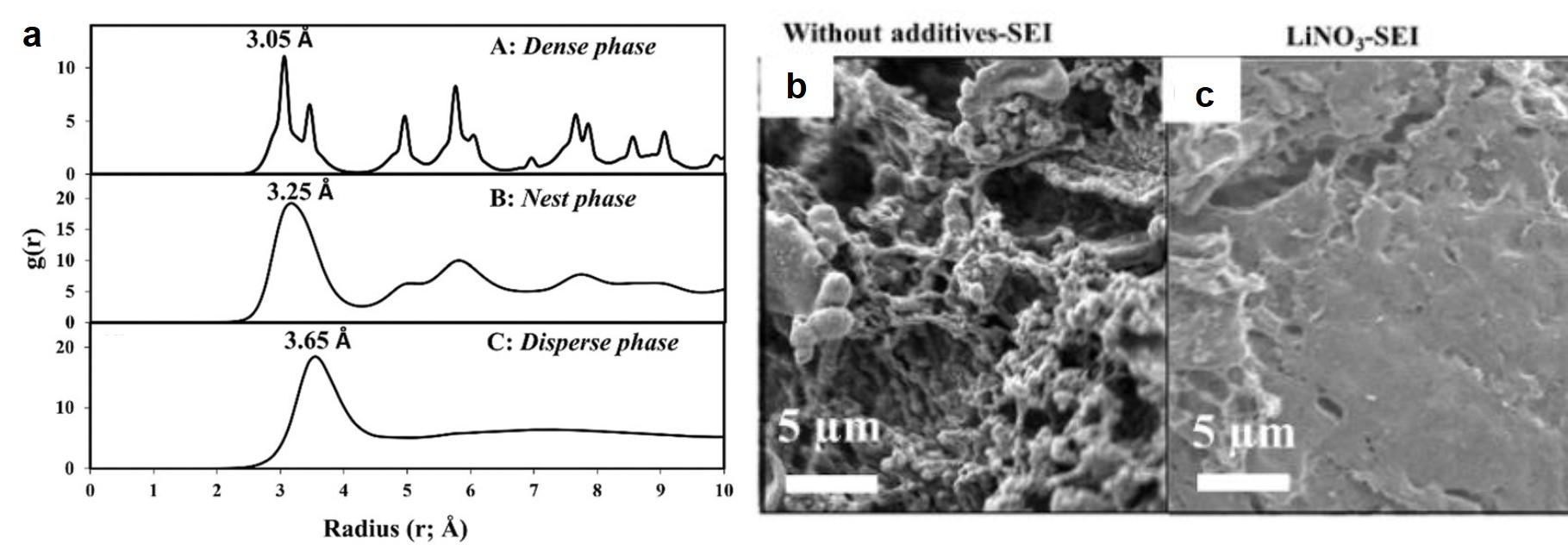

The first discovery was that LiNO3 promoted the formation of smooth, double-layered solid electrolyte interfaces (SEIs) on the Li surface. SEIs are thin layers composed of electrolyte-decomposition products, including Li-containing organic compounds and inorganic salts. By simulating the charge distribution near a Li metal surface, the authors mapped the Li-Li radial pair distribution profiles in three phases (Fig. 1a). The similarity between the profiles of the dense phase (the Li metal) and the nest phase evidenced the presence of an amorphous, Li-containing layer atop the Li metal surface. Beyond this amorphous layer was a liquid-like film with Li element distributed homogenously. This double-layered SEI altered the kinetics of Li deposition onto the Li surface upon charging, resulting in smooth and dense SEIs (Figs. 1b and c) that avoided Li dendrite formation.

Figure 1. (a) Li-Li radial pair distribution functions of the dense phase (Li metal), nest phase (the layer atop Li), and disperse phase (the outermost layer). (b and c) Top-view scanning electron microscopy images of the Li metal surface in (b) LiNO3-free and (c) LiNO3-containing electrolytes. Both electrolytes had lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) as a solute, and 1,3-dioxolane (DOL) and 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) as solvents.

Another effect of LiNO3 was to capture polysulfide compounds. Through their simulations, the authors deduced the reaction pathways involving the electrolyte molecules, LiNO3 or LiClO4 additives, and lithium polysulfide compounds (Fig. 2a). The concentration of LixNOy, the reduction products of LiNO3 when contacted Li metal, in the LiNO3-containing electrolyte was much higher than those in the additive-free and LiClO4-containing electrolytes. First-principle calculations proved that the highly electro-negative N and O atoms in LixNOy could capture lithium polysulfides via dipole-dipole interactions. This process reduced the likelihood of polysulfide reduction on Li that passivated anodes.

Figure 2. (a) A scheme of the reaction pathways involving the electrolyte, additive, and polysulfide molecules. (b) Product distributions in electrolytes without additives and with LiNO3 or LiClO4.

LiNO3 elongates the lifetimes of Li–S batteries by forming smooth SEIs to impede Li dendrite formation, while maintaining the reactivity of Li anodes by capturing lithium polysulfides.

To find out more, please read:

Insight into the Effect of Additives Widely Used in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries

Salatan Duangdangchote, Atiweena Krittayavathananon, Nutthaphon Phattharasupakun, Nattanon Joraleechanchai, and Montree Sawangphruk

Chem. Commun., 2019, 55, 13951-13954

Tianyu Liu acknowledges John Elliott of Virginia Tech, the U.S., for his careful proofreading of this post.

About the blogger:

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Commun. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at http://liutianyuresearch.weebly.com/.

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Commun. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at http://liutianyuresearch.weebly.com/.