Systems chemistry focuses on achieving controllable outputs from the interactions and reactions of a mixture of chemical components. In this way, researchers hope to mimic biological systems, which utilise highly complex series of interconnected signalling processes and feedback loops to respond to a wide range of external stimuli.

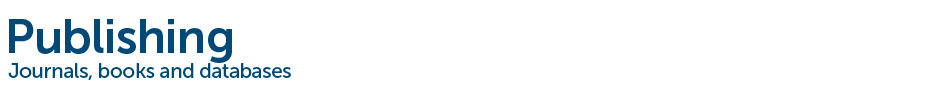

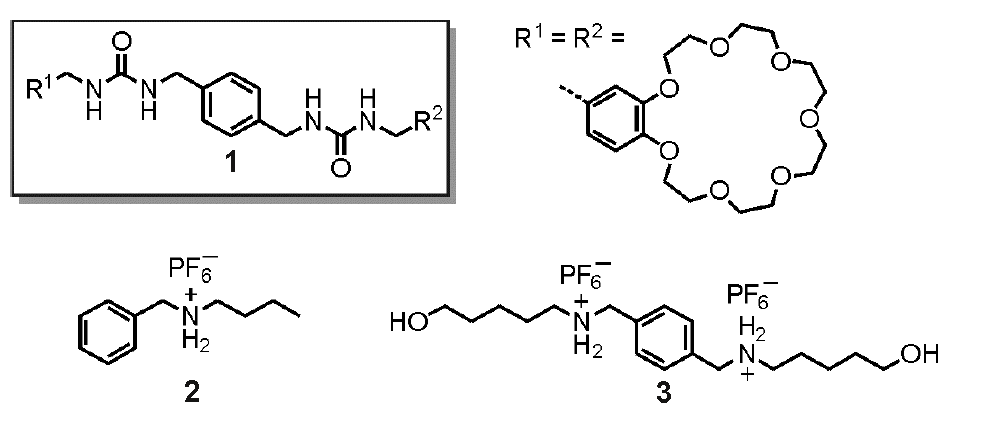

Christoph Schalley’s group in Berlin have reported a fascinating example of supramoleular systems chemistry, using a range of non-covalent interactions and self assembly properties of a simple bis-urea starting molecule. Like many bis-ureas, 1 was found to form an organogel due to hydrogen bonding interactions between the urea groups on adjacent molecules. Disrupting these interactions reverses the gel formation, leaving a sol phase. In this case, the authors found three different chemical input signals to switch the gel to a sol: adding chloride anions to hydrogen bond to the urea groups, adding potassium cations to bind within the crown ether groups, and by adding the ammonium threads 2 (2 equivalents) or 3 (1 equivalent) to form a rotaxane.

Each of these binding processes can also be reversed by chemically removing the guest, regenerating the gel phase. Silver cations were used to precipitate the chloride, a cryptand was added to tightly bind to the potassium, and the rotaxane threads were deprotonated using a base. In this way, a large number of input signals were used to yield a controllable and observable chemical property. These processes were used to construct various logic gates, in which a logic output (the formation or dissolution of a gel phase) resulted from one or more logic inputs (the addition of one or more of the above reagents).

This work uses host guest chemistry to produce real-world, observable results from a large number of chemical input signals. It is an inspiring example of how simple binding processes can be incorporated into complex sequences and systems. You can download the full article here.