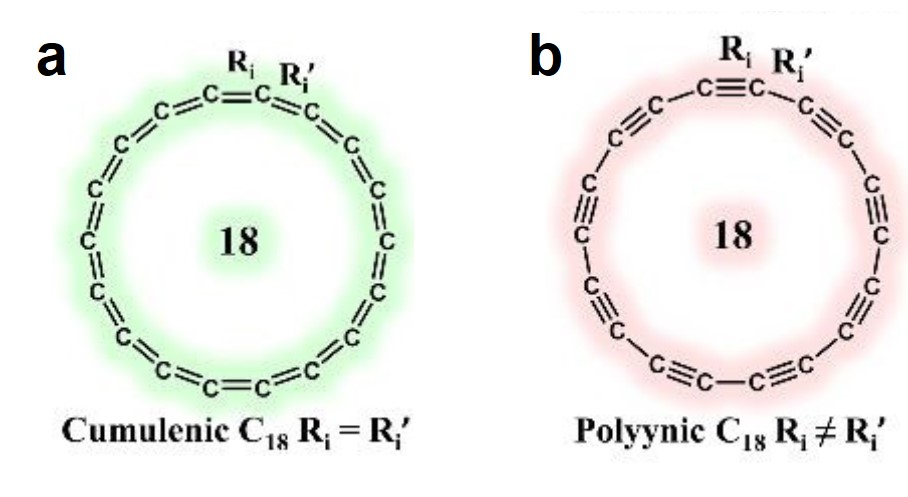

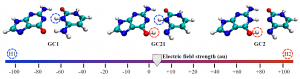

A long-lasting dispute regarding the most stable structure of cyclo[18]carbon, a new carbon allotrope, has been settled. Cyclo[18]carbon is an all-carbon ring comprised of eighteen interconnected carbon atoms. It is proposed to have two possible structures: the cumulenic structure with only carbon-carbon double bonds (Figure 1a), and the polyynic structure having alternating carbon-carbon triple and single bonds (Figure 1b). Recent experiments have confirmed that the polyynic structure is the stable form, but theorists were still puzzled: Why can’t the various computational methods reach an agreement on the molecular structure of cyclo[18]carbon?

Anton J. Stasyuk and coworkers from the University of Girona, Spain, offered an answer in ChemComm (DOI: 10.1039/C9CC08399E). They found that the simulated structure strongly depended on the type of functionals used in density functional theory (DFT), which is a computational tool to derive energy-minimum molecular structures. The functionals used for DFT calculations are mathematical terms that can tune the simulation accuracy.The authors discovered that the weight of the exact exchange term (HF% exchange) in the DFT functionals determined the most stable simulated structure of cyclo[18]carbon. The researchers compared 13 functionals with various percentages of HF% exchanges. They found that functionals with the HF% exchange higher than 50% predicted the appreciably different lengths of the neighboring bonds (quantified as the bond length alternation, the vertical axis of Figure 2), corresponding to the polyynic structure (Figure 2, red zone). This structure was recently observed experimentally. Functionals with lower HF% exchange either obtained the cumulenic structure (Figure 2, green zone) or the mixed cumulenic-polyynic structure (Figure 2, gray zone).

Figure 2. Variation in the HF% exchange of the B3LYP functional changed the predicted molecular structure of cyclo[18]carbon. BLA: Bond length alternation.

To find out more, please read:

Cyclo[18]Carbon: Smallest All-Carbon Electron Acceptor

Anton J. Stasyuk, Olga A. Stasyuk, Miquel Solà, and Alexander Voityuk

Chem. Commun., 2019, DOI: 10.1039/C9CC08399E

Tianyu Liu acknowledges Zac Croft at Virginia Tech, U.S., for his careful proofreading of this post.

About the blogger:

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Comm. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at http://liutianyuresearch.weebly.com/.

Tianyu Liu obtained his Ph.D. (2017) in Chemistry from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the United States. He is passionate about the communication of scientific endeavors to both the general public and other scientists with diverse research expertise to introduce cutting-edge research to broad audiences. He is a blog writer for Chem. Comm. and Chem. Sci. More information about him can be found at http://liutianyuresearch.weebly.com/.