A high-power ultrasonic microreactor and its application in gas-liquid mass transfer intensification

Chemically induced coalescence in droplet-based microfluidics

An Optopneumatic Piston for Microfluidics

New YouTube Videos

Cytometry Unplugged: acoustophoretic focusing enables impedance-based particle sizing and counting

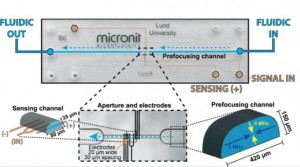

Groups collaborating across Sweden, Denmark, and Korea develop a chip-integrated acoustic focusing technique to precisely arrange particles for fast sizing and counting using impedance analysis.

The size and number of particles in a mixture can be quickly determined using a Coulter counter. Changes in resistance across a Coulter counter orifice through which particles pass correspond to the volume particles occupy as they displace the ionic carrier fluid (impedance spectroscopy). As fabrication methods transition to planar electrode formats to facilitate device development, the precise position of particles in the orifice becomes crucial to obtaining accurate results. Using planar electrodes on the channel bottom, the electric field across the orifice varies and thus sizing information from amplitude changes in impedance depend on consistent particle positioning. Previous methods using fluid flow focusing require complex fabrication steps and suffer from ion diffusion between virtual channel boundaries (fluid-fluid interfaces). Thus, Carl Grenvall in the Biomedical Engineering department in Lund University and his colleagues developed an acoustic actuation method to focus particles into the middle of the channel before they pass into the sensing aperture containing planar electrodes.

The team used two different frequencies to form standing waves in horizontal and vertical directions of the ‘prefocusing channel’ to guide particles to the center of the aperture where impedance was analyzed. Concentration studies helped determine the optimal density of particles to enable rapid sample analysis yet prevent formation of doublets. Confocal imaging confirmed simulation results to show distribution of focused particles and narrow confinement – 2.04% coefficient of variation after removing doublets, which is on par with other experimental and commercial cytometry platforms. The group was able to discriminate particle sizes from 3, 5, and 7 μm as well as separate 7 μm beads in a diluted blood sample. This demonstration of efficient particle focusing in two dimensions is an exciting development to create integrated simple-to-manufacture microchip impedance microscopy platforms. Standing wave acoustophoresis is gentle on cells as several studies even reporting in-field cell culturing1, thus suggesting further opportunities for integration of microscale cytometers into microscale experimental platforms.

Download the full paper for free* for a limited time only!

Two-dimensional acoustic particle focusing enables sheathless chip Coulter counter with planar electrode configuration

Carl Grenvall, Christian Antfolk, Christer Zoffmann Bisgaard, and Thomas Laurell. Lab Chip, 2014, 14, 4629 – 4637.

DOI: 10.1039/c4lc00982g

*Access is free through a registered publishing personal account until 03/02/2015.

[1] M. A. Burguillos, C. Magnusson, M. Nordin, A. Lenshof, P. Augustsson, M. J. Hansson, E. Elmer, H. Lilja, P. Brundin and T. Laurell, PloS one, 2013, 8, e64233.

New YouTube videos

Measuring Electrical Resistance in Organs-on-Chips

The human body contains many barriers, like the skin, the wall of blood vessels, or the lining of the intestine. Understanding and quantifying the barrier function of human tissues is of great biomedical importance. Just think of wounds, hemorrhage, pulmonary edema and intestinal infections. All of them involve the breakdown of a barrier in the human body.

The quantification of barrier function of cell layers can be carried out in the laboratory by measuring their resistance to an electrical potential difference. When applying such a potential difference over a layer of tissue, ions in the solution start moving, which leads to an electrical current. The tighter the tissue barrier, the more difficult it is for ions to pass through, the higher the electrical resistance will be. Measuring the electrical resistance of cell layers is a popular tool in conventional cell culture. However, it has proven difficult to use the same tool in microfluidic cell culture systems, such as organs-on-chips.

Measuring electrical resistance of cell layers in organs-on-chips is difficult, because the devices only contain small amounts of water and ions, which means they will have a very high electrical resistance to begin with. This means that the resistance of a layer of cells is only a very small portion of the total resistance of the system. But even when being careful to perform a measurement that is sensitive enough to detect the small contribution of the cell layer to the total system resistance, it turns out that the resistance values for cells in such small devices don’t match the values that we find in conventional cell culture systems.

In a recent paper in Lab on a Chip, written by dr. Mathieu Odijk, myself and others, we show that the apparent electrical resistance of a cell layer in an organ-on-a-chip will be much higher than that of a cell layer in a conventional cell culture system. The underlying cause for this high apparent electrical resistance is rooted – again – in the high electrical resistance of microfluidic compartments.

An electrical potential that is applied at the start of a microfluidic compartment will drop significantly over the length of that compartment. This means that large parts of a cell layer that separates two microfluidic compartments will not be exposed to a significant potential difference anymore (see also schematic image on the left). Because we effectively only measure small parts of the cell layer and because small areas will by definition not conduct as much current as large areas, we will find a pretty high apparent value for the electrical resistance of the cell layer in an organ-on-a-chip. If we then make the mistake of assuming that this electrical resistance is produced by a barrier to which all cells in the layer have contributed equally, we will overestimate the tightness, resistance, barrier function of this cell layer.

Fortunately, the issue of overestimating the electrical resistance of cell layers in organs-on-chips can be resolved by calculating the effective area of the cell layer that contributes to the measured resistance. We apply this method to normalize the electrical resistance signal produced by a layer of epithelium in an organ-on-a-chip systems that mimics the human intestine. We show that after normalization, the resistance of the epithelium in this ‘gut-on-a-chip’ is the same as the resistance values that were found in standard cell culture systems.

Measuring barrier function in organs-on-chips is still tricky business, but the work in this article brings reliable measurements a step closer. Go check it out:

Odijk, et al. Measuring direct current trans-epithelial electrical resistance in organ-on-a-chip microsystems.

Access is free through a registered publishing personal account until 02/02/2015.

November’s Free HOT Articles

These HOT articles, published in Novemeber 2014 were recommended by our referees and are free* to access for 4 weeks

From cellular lysis to microarray detection, an integrated thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) point of care Lab on a Disc

Emmanuel Roy, Gale Stewart, Maxence Mounier, Lidija Malic, Régis Peytavi, Liviu Clime, Marc Madou, Maurice Bossinot, Michel G. Bergeron and Teodor Veres

Lab Chip, 2015,15, 406-416

DOI: 10.1039/C4LC00947A, Paper

Inkjet-printed microelectrodes on PDMS as biosensors for functionalized microfluidic systems

Jianwei Wu, Ridong Wang, Haixia Yu, Guijun Li, Kexin Xu, Norman C. Tien, Robert C. Roberts and Dachao Li

Lab Chip, 2015, Advance Article

DOI: 10.1039/C4LC01121J, Paper

Electrochemical pesticide detection with AutoDip – a portable platform for automation of crude sample analyses

Lisa Drechsel, Martin Schulz, Felix von Stetten, Carmen Moldovan, Roland Zengerle and Nils Paust

Lab Chip, 2015, Advance Article

DOI: 10.1039/C4LC01214C, Paper

Take a look at our Lab on a Chip 2014 HOT Articles Collection!

A new challenge for children: getting rid of pathogens from water using microfluidics

Dr Loes Segerink writes about a Focus Article recently published in Lab on a Chip…

The use of microfluidics to test the safety of drinking water is growing increasingly. Although several microfluidic concepts are already shown to detect pathogens in water useful for this industry, the authors of this article focus on the use of such a device for a different audience: young children. They show that it can be perfectly used as an educational tool to make children more aware of the importance of clean water and the advantages of microfluidics.

water useful for this industry, the authors of this article focus on the use of such a device for a different audience: young children. They show that it can be perfectly used as an educational tool to make children more aware of the importance of clean water and the advantages of microfluidics.

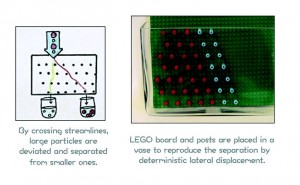

In total six modules are developed, each of them having own teaching objectives and materials. The modules can be used separately and both standardized techniques as well as new microfluidic techniques are treated. For instance the use of the microfluidic separation technique deterministic lateral displacement to separate pathogens out of the water is visualized on a macroscale using LEGO® and particles made with FIMO® clay. The good particles are smaller in diameter than the bad ones, making separation in on macroscale using viscous media (in this case shower gel) possible.

A complete activity is made by the authors, that shows a new and original approach to make young children aware of the challenges in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. By using simple components in combination with cartoons and descriptions, the child can remove the bad pathogens from drinking water in about 30 minutes.

For more information, download the full article now – access is free* for a limited time only!

Angry Pathogens, how to get rid of them: introducing microfluidics for waterborne pathogen separation to children

Melanie Jimenez and Helen L.Bridle

DOI: 10.1039/C4LC0944D

* Access is free through a registered RSC account until 23rd January 2015.

About the webwriter

Dr Loes Segerink is an Assistant Professor in the BIOS Lab-on-a-Chip Group at the University of Twente. Read more about her research interests on her homepage.