The human body contains many barriers, like the skin, the wall of blood vessels, or the lining of the intestine. Understanding and quantifying the barrier function of human tissues is of great biomedical importance. Just think of wounds, hemorrhage, pulmonary edema and intestinal infections. All of them involve the breakdown of a barrier in the human body.

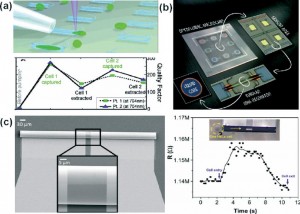

The quantification of barrier function of cell layers can be carried out in the laboratory by measuring their resistance to an electrical potential difference. When applying such a potential difference over a layer of tissue, ions in the solution start moving, which leads to an electrical current. The tighter the tissue barrier, the more difficult it is for ions to pass through, the higher the electrical resistance will be. Measuring the electrical resistance of cell layers is a popular tool in conventional cell culture. However, it has proven difficult to use the same tool in microfluidic cell culture systems, such as organs-on-chips.

Measuring electrical resistance of cell layers in organs-on-chips is difficult, because the devices only contain small amounts of water and ions, which means they will have a very high electrical resistance to begin with. This means that the resistance of a layer of cells is only a very small portion of the total resistance of the system. But even when being careful to perform a measurement that is sensitive enough to detect the small contribution of the cell layer to the total system resistance, it turns out that the resistance values for cells in such small devices don’t match the values that we find in conventional cell culture systems.

In a recent paper in Lab on a Chip, written by dr. Mathieu Odijk, myself and others, we show that the apparent electrical resistance of a cell layer in an organ-on-a-chip will be much higher than that of a cell layer in a conventional cell culture system. The underlying cause for this high apparent electrical resistance is rooted – again – in the high electrical resistance of microfluidic compartments.

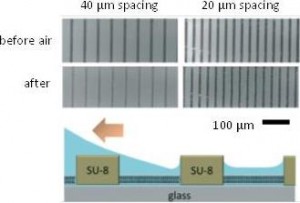

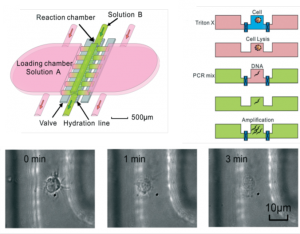

An electrical potential that is applied at the start of a microfluidic compartment will drop significantly over the length of that compartment. This means that large parts of a cell layer that separates two microfluidic compartments will not be exposed to a significant potential difference anymore (see also schematic image on the left). Because we effectively only measure small parts of the cell layer and because small areas will by definition not conduct as much current as large areas, we will find a pretty high apparent value for the electrical resistance of the cell layer in an organ-on-a-chip. If we then make the mistake of assuming that this electrical resistance is produced by a barrier to which all cells in the layer have contributed equally, we will overestimate the tightness, resistance, barrier function of this cell layer.

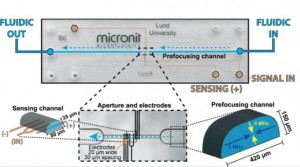

Fortunately, the issue of overestimating the electrical resistance of cell layers in organs-on-chips can be resolved by calculating the effective area of the cell layer that contributes to the measured resistance. We apply this method to normalize the electrical resistance signal produced by a layer of epithelium in an organ-on-a-chip systems that mimics the human intestine. We show that after normalization, the resistance of the epithelium in this ‘gut-on-a-chip’ is the same as the resistance values that were found in standard cell culture systems.

Measuring barrier function in organs-on-chips is still tricky business, but the work in this article brings reliable measurements a step closer. Go check it out:

Odijk, et al. Measuring direct current trans-epithelial electrical resistance in organ-on-a-chip microsystems.

Access is free through a registered publishing personal account until 02/02/2015.