Written by Mark Archibald.

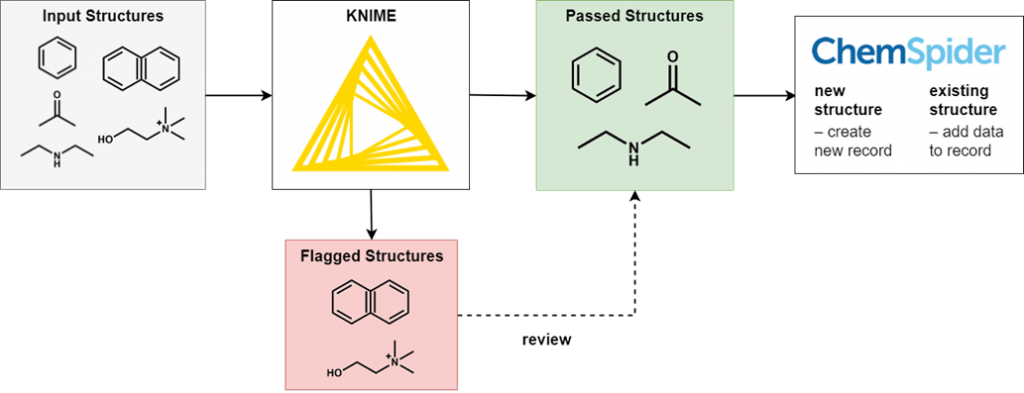

In a previous post (Behind the Scenes at ChemSpider) we discussed some of the challenges in upholding data quality across one of the largest chemical databases in the world. We identified automated filtering as a key tool when dealing with far more records than a human could reasonably handle. In this post we’ll go into more detail about how that filtering works, what the challenges are, and the role played by human intervention.

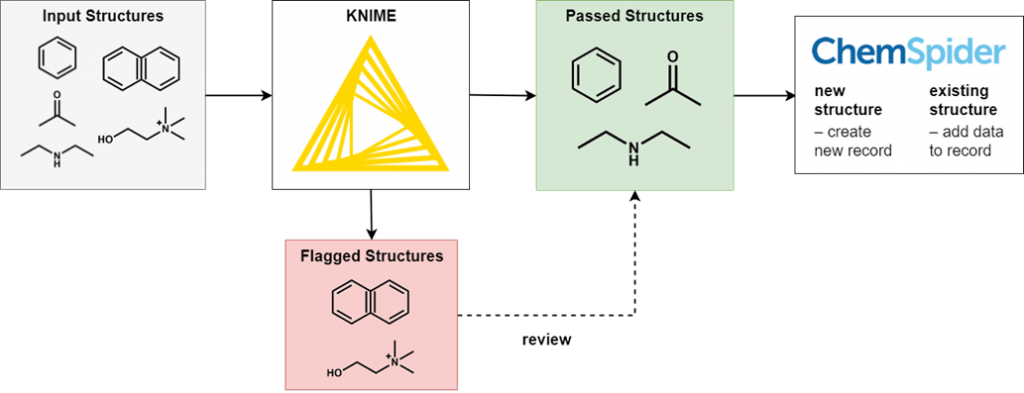

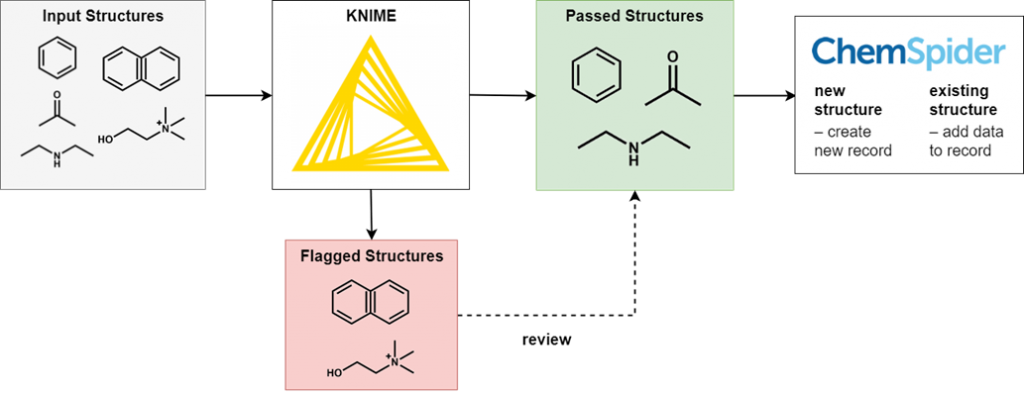

To perform this filtering we use KNIME, an open-source data processing platform. The wide range of KNIME nodes developed by the active cheminformatics community allows us to ask chemistry-specific questions of the data we process. In simple terms, input chemical structures that match our criteria are passed on to the next node, while those that don’t are written out to an error file. After processing all structures, the result is a file of structures that have successfully passed through all the filters and several (usually smaller) files of structures rejected for various reasons.

It’s not possible to review all of the generated files in full, as this would eliminate the time-saving advantages of automated processing. However, output files of all types are spot checked for accuracy and to iteratively improve the filtering criteria. Certain output files have high potential for false positives and so we review them in full.

Formats and identifiers

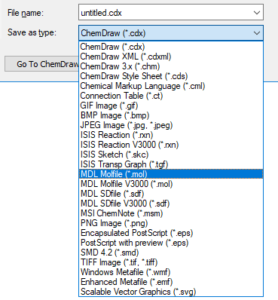

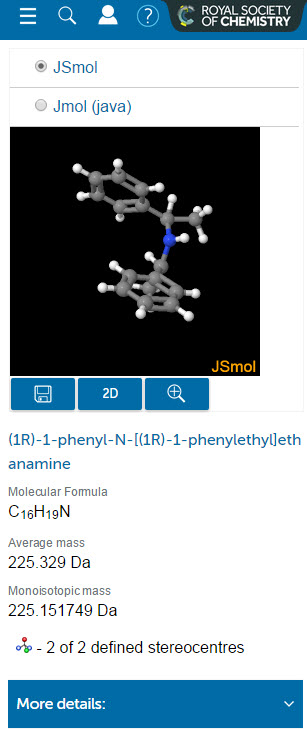

Submitted files can be in one of several different formats. The most common is SDF (structure data file, a chemical structure format containing multiple structures with associated data fields). The advantage of this format is that it contains 2- or 3-dimensional structures, so we can immediately start processing the file without having to convert an identifier to a structure. This means that the final structure we deposit is more likely to exactly match the original. The disadvantage of the SDF format is that it is specialised – many users will be unfamiliar with it or won’t have software to create and display the files.

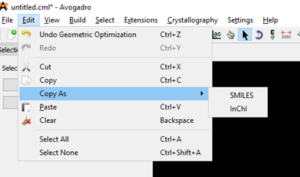

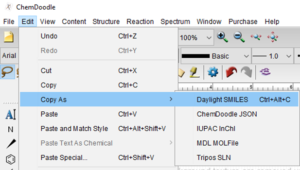

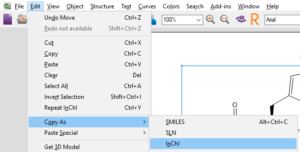

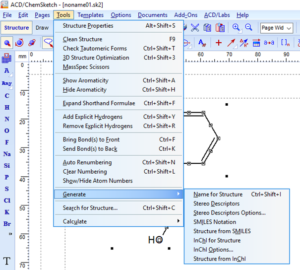

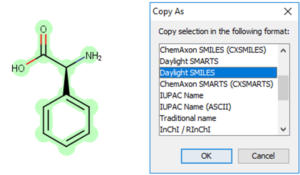

We also receive different spreadsheet formats (excel, csv, tsv) with structures encoded in text-based notation systems like SMILES or InChI. The advantage of this format is that it doesn’t require specialised software (provided the submitter has SMILES or InChIs for the compounds).The disadvantage is that the structures require conversion to SDF before processing and deposition to ChemSpider. Additionally, these formats contain information about atoms and their connectivity but lack layout information. This can introduce errors as different structure drawing packages can parse these structures slightly differently, resulting in alterations to the final deposited structure.

Filtering criteria

The criteria by which we judge chemical structures are a mixture of definitive chemical rules and less well-defined ‘rules of thumb’ based on our experience and chemical knowledge. Examples of both follow.

Empty structures, query atoms and incorrect valences

The first filter is the simplest – ChemSpider is a structure-centric database, so it’s not possible to deposit any input entries that lack a structure.

Similarly, each ChemSpider record requires a single defined chemical structure, so we exclude anything using a query atom to represent a variable atom or attachment point.

Another simple filter is to exclude structures in which atoms have invalid valences.

Charge imbalance

In general, entries in ChemSpider should represent a real-world, isolable compound. This means that we filter out structures with a non-zero overall charge. However, we make exceptions for certain examples where a counterion is generally unimportant and it’s useful to consider the charged species alone, such as choline (ChemSpider record).

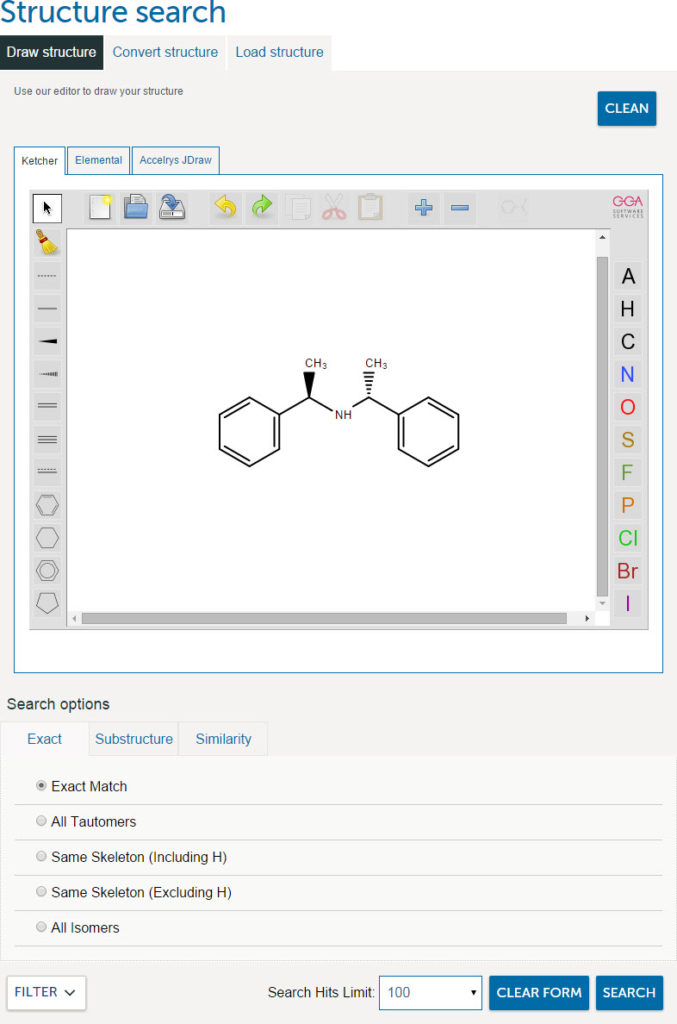

Structures containing undefined stereocentres

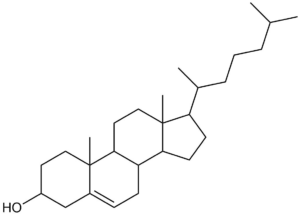

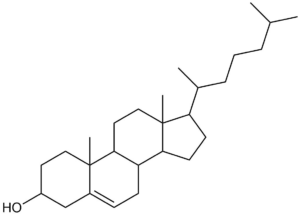

Undefined stereocentres alone don’t represent a chemical error. However, structures like that shown below (cholesterol without any defined stereocentres) occur frequently and, although chemically valid, it’s extremely unlikely that they represent the intended structure.

Cholesterol skeleton without stereochemistry

As a result we have a rule of thumb that excludes structures containing more than two undefined stereocentres. This is not a hard-and-fast rule, but rather an attempt to strike a balance between excluding structures like the one above and including structures where the undefined stereocentres are intentional and correct.

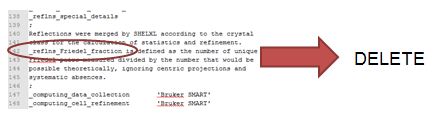

The count of undefined stereocentres (as determined by examining the InChI) sometimes includes cases where it is conventional to exclude stereochemical wedges. Examples include nucleic acids with no wedges on the phosphate and adamantyl groups without explicit stereochemistry – it’s unusual to draw these compounds with wedges, and users will rarely use wedges in their search. These potential false positives are filtered out and reviewed manually. A curator can then decide whether to include them in the deposition, improving the overall accuracy of the filter.

Structures containing many components

This is another rule of thumb – there’s no upper limit on how many separate components a correctly depicted chemical substance can have. However, from experience we find that excluding structures with more than four separate components removes most obviously nonsensical entries (e.g. attempts to depict alloys) while retaining the majority of correct entries.

When applying this rule, pharmaceutical molecules represent a major source of false positives because they are often multiple hydrates and/or salts with multiple counterions (e.g. Irinotecan hydrochloride trihydrate). Excluded structures that are hydrates or contain common pharmaceutical salts are flagged for human review.

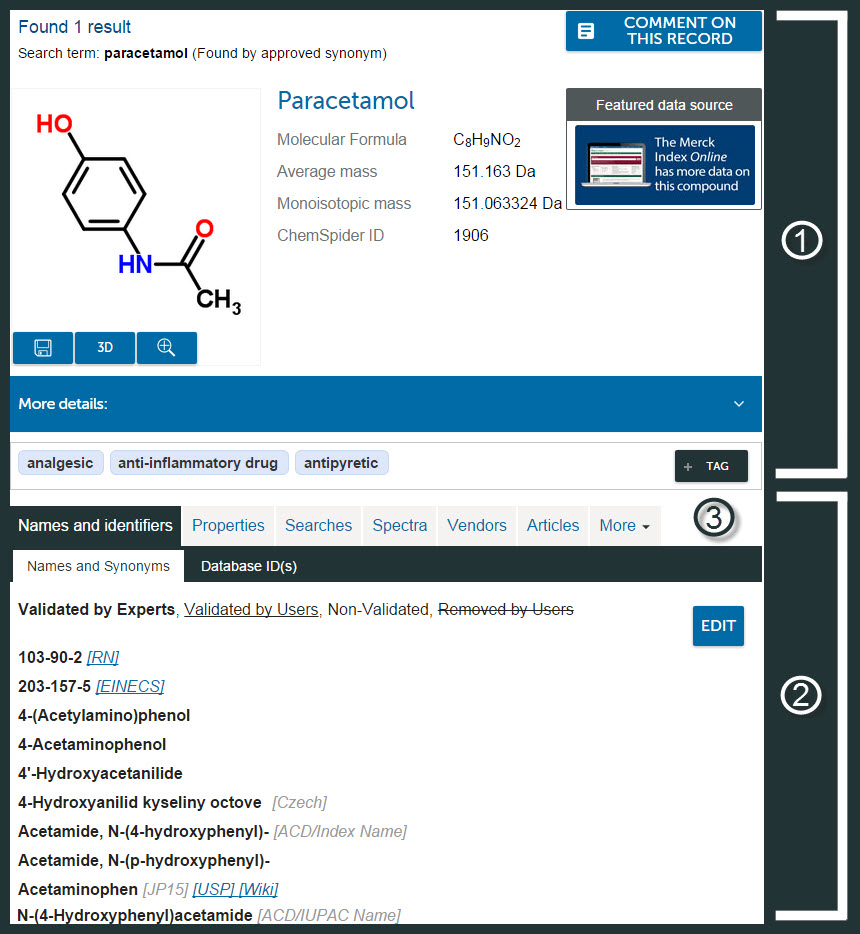

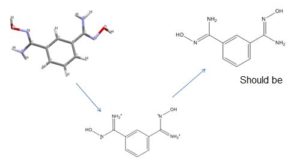

Synonym filter

This filter compares the synonyms assigned to a given structure with its molecular formula and performs some ‘common sense’ checks. For example, a relatively frequent error is associating the name of a salt form (e.g., mozavaptan hydrochloride) with the structure of the free base (mozavaptan). In this case, the filter removes synonyms containing ‘hydrochloride’ because the molecular formula does not contain Cl.

SMARTS

SMARTS (Wikipedia page) is a way of describing general chemical structures. It’s based on SMILES, but has additional features allowing the specification of variable chain lengths, number of bonds, number of hydrogens, variable bond orders, or more than one potential element at a site.

We use SMARTS to identify common erroneous features in a structure. These include:

- Azides and diazo groups depicted with a pentavalent nitrogen

- A ‘floating’ alkane unconnected to the main structure (probably caused by an accidental click in a drawing program)

- Metal carboxylates depicted as a protonated carboxylic acid with an elemental metal atom

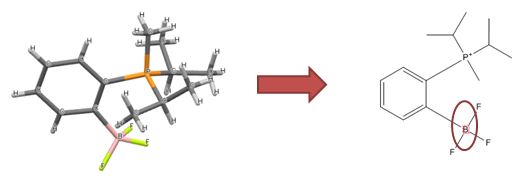

- Hexafluorophosphates (and similar species) depicted as phosphorous pentafluoride and a separate fluoride ion

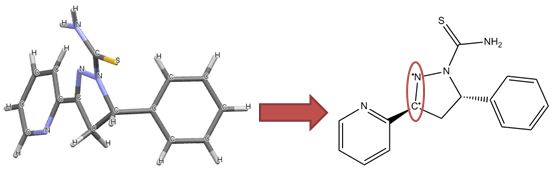

SMIRKS

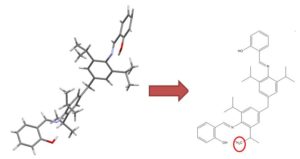

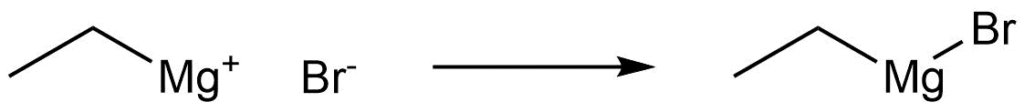

SMIRKS is a further extension of SMILES to depict reactions. We don’t use it to represent real reactions, but to define structural transformations – allowing us to fix simple structural errors that can be resolved by breaking and creating bonds.

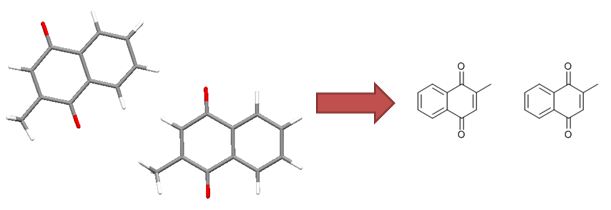

One example is connecting charge-separated Grignard reagents to give a more accurate depiction:

Reconnecting Grignards

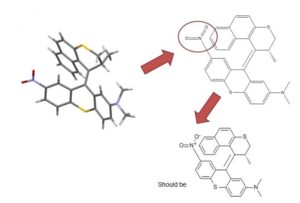

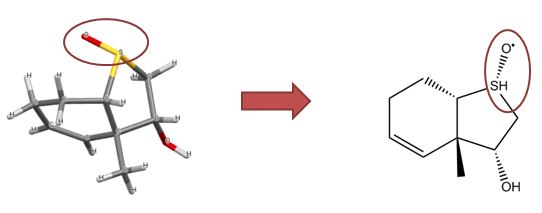

Organometallics

The difficulties of encoding organometallic structures in machine-readable formats are well documented (J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51, 12, 3149-3157). There is an ongoing IUPAC project to extend the InChI’s functionality, but for now, the challenges remain.

Every ChemSpider record is fundamentally based on an InChI, and so we are bound by the current limitations. This means that we can’t depict coordination bonds or bonds with non-integer order – any bond drawn is interpreted as a standard covalent bond with one electron contributed by each atom.

Although we generally can’t represent organometallic structures in the manner a human chemist would prefer, we still attempt to choose the ‘least wrong’ structure from various possible compromises.

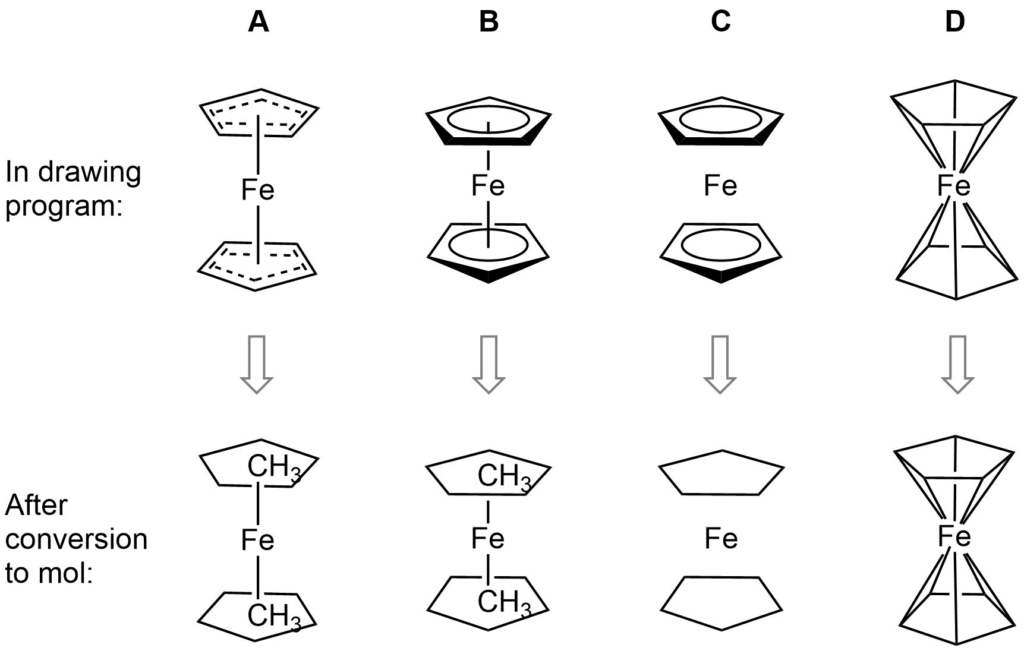

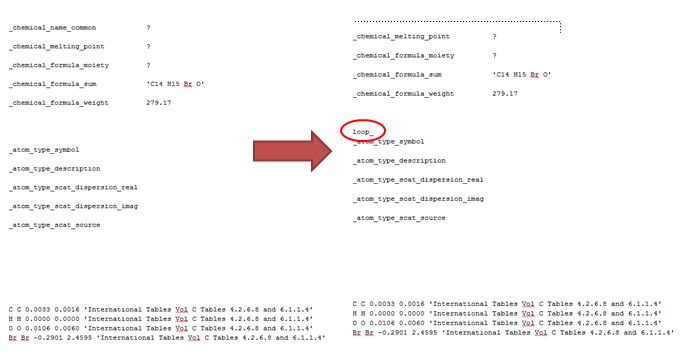

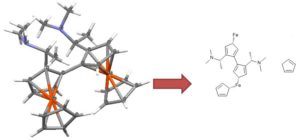

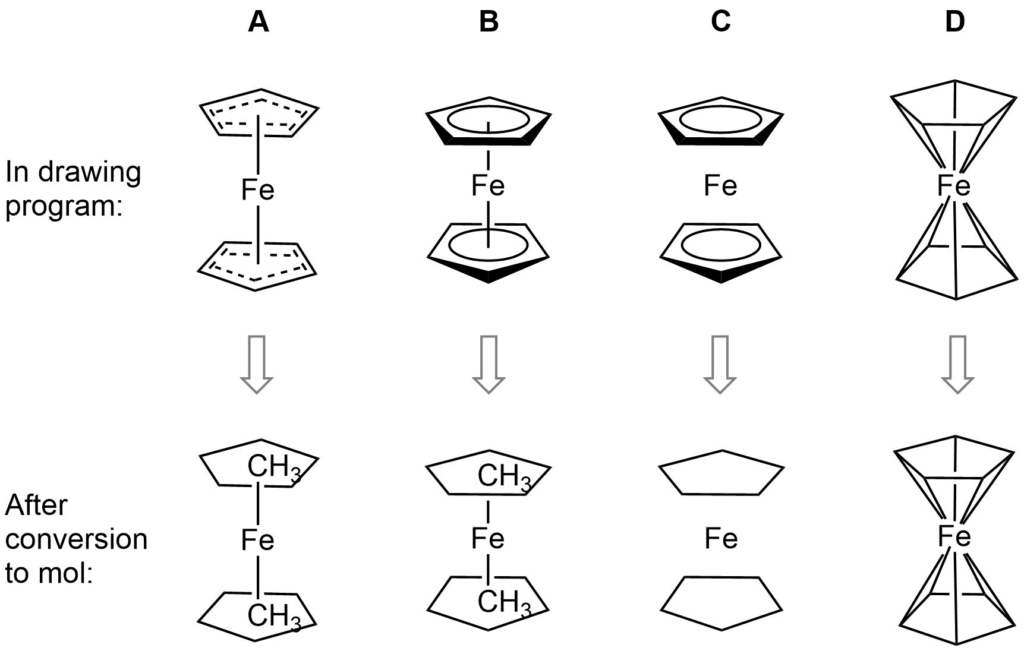

Ferrocene is a classic example of this problem and illustrates several of the issues we have to consider. A few common ways to draw ferrocene are shown below (there are many more).

Converting ferrocene structures to mol format can introduce errors in molecular formula, bond orders or valence

Most of the structures shown take advantage of extended features of chemical drawing packages in order to represent ferrocene’s bonding in a way that’s attractive and easily understandable to a human chemist. Unfortunately, once transferred to the simplified but universal mol format, some of those features are lost, resulting in nonsensical structures. Although structure D is unchanged, this representation has other problems: incorrect valence on Fe and no representation of the aromaticity of the cyclopentadienyl ligands.

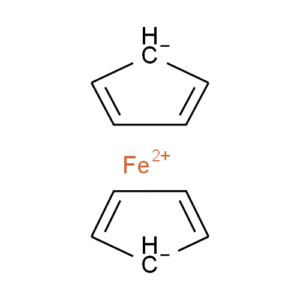

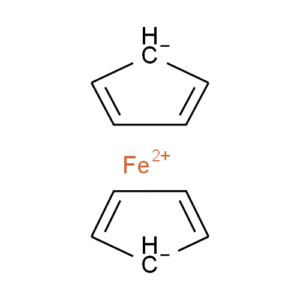

We have a limited number of ways in which we can depict ferrocene and related structures in ChemSpider, none of which give an accurate representation of the bonding or a view that would satisfy an inorganic chemist. However, we can choose the ‘least bad’ of the possible compromises and allow machine readability:

Our compromise

Although this structure (ChemSpider record) doesn’t capture the hapticity of ferrocene and the charge localisation on a single carbon is inaccurate, it retains correct overall charges and valences and doesn’t show the ligands as sigma-bonded.

More generally, we apply some rules and transformations to standardise representations of organometallic structures. Many of these rules involve choosing whether to depict a metal–carbon (or metal–heteroatom) as covalent or ionic, depending on the nature of the metal and the ligand. Again, compromises are necessary when working within the limitations of machine-readable structures, but we attempt to classify ‘more ionic’ and ‘more covalent’ bonds. Some examples follow:

- Disconnect oxygen from group 1 and 2 metals

- Connect oxygen to all other metals

- Disconnect carbon from sodium, potassium and calcium

- Connect carbon to group 11 and 12 metals, p-block metals and some metalloids

As expected, general rules like these fail in certain cases. Therefore we have additional, more specific rules to cover exceptions, which we iteratively refine.

But these errors still appear in ChemSpider!

At present the filtering described only applies to new data coming into ChemSpider. The full ChemSpider database, built up over many years, certainly contains examples of every error described here. To fix these legacy errors, we intend to run the entire database through the same quality filters. This is a significant task with some specific challenges: the files requiring human review become orders of magnitude larger, the processing time and memory/CPU overhead is high, and the larger the data set the more likely we will run into false positives. In order to manage these challenges, we are taking the time to refine our processes on new depositions, and periodically checking our progress by running subsets of the full ChemSpider database through our filters. We know you need access to data you can trust, so we want to make sure we get this right. We’ll continue to update you as this project progresses, so stay tuned!

Comments Off on ChemSpider Pre-Deposition Filters

![]()