On-demand droplet splitting using surface acoustic waves

A microfluidic cell-trapping device for single-cell tracking of host–microbe interactions

The physical origins of transit time measurements for rapid, single cell mechanotyping

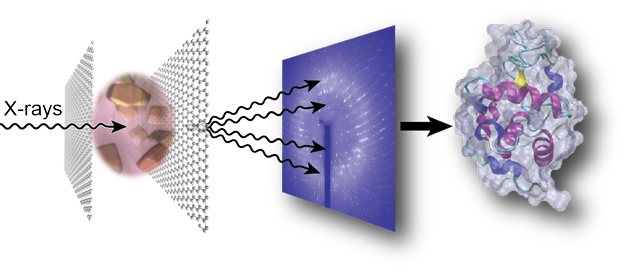

Introducing graphene into microfluidic devices can make it easier to study proteins at an atomic level, scientists in the US have shown. Devices that are thinner and interfere less with the measurements allow larger and more intricate protein structures to be resolved using techniques that rely on probing thousands of microcrystals.

Not only does this reduce the device’s thickness, improving the signal-to-noise ratio, the graphene also acts as a barrier to prevent the sample evaporating. John Helliwell, an expert in crystallography at the University of Manchester in the UK, explains that preventing water loss from the crystal is ‘vital…because the sample hydration state needs to be preserved for its molecular integrity’.

Perry’s group are now focusing on shrinking down the dimensions and increasing the complexity of the device, as well as studying the structure of proteins involved in programmed cell death.

To read the full article visit Chemistry World.

Click the link below to read the original research paper published in Lab on a Chip for free*:

Graphene-based microfluidics for serial crystallography

Shuo Sui, Yuxi Wang, Kristopher W. Kolewe, Vukica Srajer, Robert Henning, Jessica D. Schiffman, Christos Dimitrakopoulos and Sarah L. Perry

Lab Chip, 2016, Advance Article

DOI: 10.1039/C6LC00451B

*Article is free to access until 26/07/2016 through a RSC registered account – click here to register

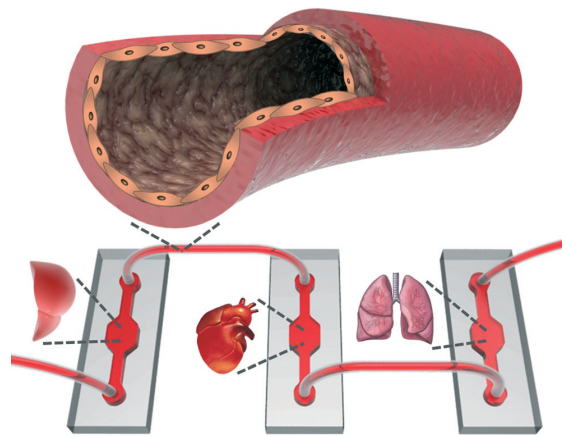

It takes about 14 years and 2 billion dollars to bring a successful drug from laboratory to clinic. A large portion of this time period includes in vitro culture tests, animal tests, and clinical trials. The overall success rate of a new drug molecule making it through this entire process is only around 10%. To improve this situation, there has been a tremendous amount of work in recent years on developing in vitro organ-on-chip models. Many organ-on-chip platforms (including heart, lung, kidney, liver, and intestine) have shown to mimic organ functions on the microscale, offering the possibility to eliminate animal testing, shorten long development times, and reduce costs. More importantly, such platforms can offer personalized medicine, enabling drug molecules to be tested directly on individual patient cells without adverse side-effects or harm.

Although existing organ-on-chip models have been shown to function well individually, integrating all models into a single fluidic circuitry (or “body-on-a-chip”) remains a necessary goal to recapitulate multi-physiological functions (Figure 1). Passive tube connections and chip-based vessels have thus far been utilized for this purpose. However, bulky dead volumes created in connections, and unbalanced scaling of the volumes between organ models and chip-based vessels, seem counterintuitive to the miniaturized nature of microscale platforms. These methods may also result in miscommunication between the organ models due to the dilution of the signal molecules secreted by the cells.

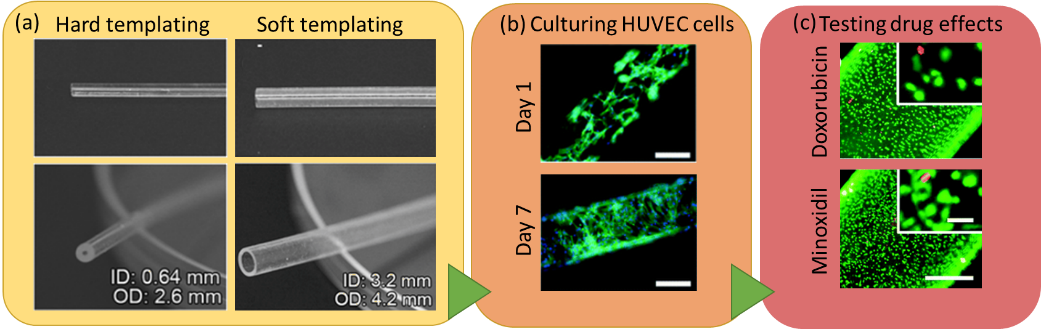

This fundamental problem has recently been addressed in a practical way by Khademhosseini and co-workers, who are the first to develop polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) hollow tubes in a range of different sizes and wall thicknesses which mimic the physio-anatomical properties of blood vessels. The fabrication of the PDMS tubes was enabled by two different strategies, including both hard and soft templating (Figure 2a). After fabrication, the tube’s interior surface was coated with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) to introduce biological functions (Figure 2b). The biofunctionality of the elastomeric blood vessels was demonstrated by the expression of an endothelial biomarker and dose-dependent responses in the secretion of von Willebrand factor. The endothelialized PDMS tubes were also utilized for assessing a panel of drugs, including the anti-cancer drug doxorubicin, immunosuppressive drug rapamycin, and vasodilator medication minoxidil, as well as amiodarone, acetaminophen, and histamine (Figure 2c). Functional elastomeric blood vessels can be fabricated up to 20 cm in length, which is sufficient for interconnecting the organ-on-chip models. Moreover, tailorable wall thicknesses enable the opportunity to study various disease models, such as the effect of diabetes or hyperlipidemia on blood vessels. The elastomeric blood vessels are expected to replace the current technologies in assembling human organ-on-chip models.

Figure 2. (a) The elastomeric PDMS blood vessels fabricated using hard and soft templating. (b) A blood vessel template with 0.28 mm diameter is used to culture HUVEC. F-actin (green) and DAPI (blue) staining are performed to visualize the cytoskeletons and the nuclei of the cells. Scale bars are 200 μm. (c) The cell growth in the templates are further shown by live (green) and dead (red) staining under application of several drugs, including Doxorubicin (anti-cancer drug) and Minoxidil (a vasodilator usually used for treatment of severe hypertension). Scale bars are 50 μm.

To download the full article for free* click the link below:

Elastomeric free-form blood vessels for interconnecting organs on chip systems

Weijia Zhang, Yu Shrike Zhang, Syeda Mahwish Bakht, Julio Aleman, Kan Yue, Su-Ryon Shin, Marco Sica, João Ribas, Margaux Duchamp, Jie Ju, Ramin Banan Sadeghian, Duckjin Kim, Mehmet Remzi Dokmeci, Anthony Atala, and Ali Khademhosseini

Lab Chip, 2016, 16, 1579-1586

DOI: 10.1039/C6LC00001K, Advance Article

—————-

Burcu Gumuscu is a PhD researcher in BIOS Lab on a Chip Group at University of Twente in The Netherlands. Her research interests include development of microfluidic devices for second generation sequencing, organ-on-chip development, and desalination of water on the micron-scale.

—————-

*Access is free until 17/06/2016 through a registered RSC account.