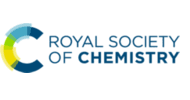

Mice, fruit fly, zebra fish easily come to mind when thinking of animal models for human physiology studies – but one animal is often forgotten, although it is as functional as the others. Have you guessed already? We are talking about soil-dwelling worms, aka C. elegans! These animals combine the simplicity of single-cell systems with the complexity of animal models, therefore they can provide significant insights into human disorders. Please take a moment to look at our note below summarizing the key features of C. elegans.

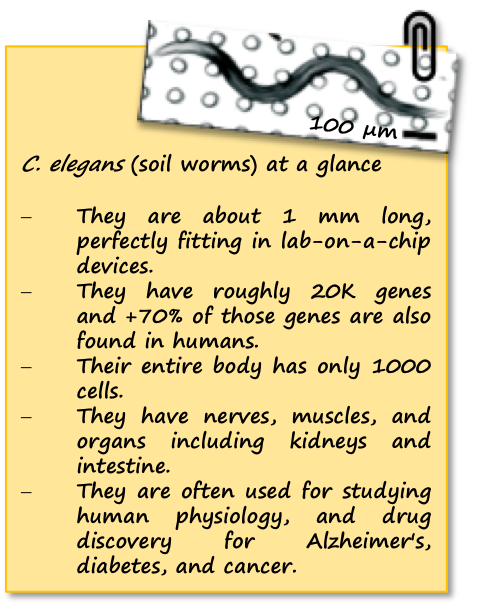

Muscular strength is a good example of human physiology studies and it relies on calcium-initiated muscle contraction, sarcomere composition and organization, and translocation of actin and myosin molecules. Analysis of such parameters can reveal the formation of muscular dystrophy, a muscle degenerative disorder. However, the measurement of these parameters has been a challenge due to the dependence on random animal-behavior that yields irreproducible results. Recently, researchers from Texas Tech University collaborated with Rutgers University and University of Nottingham to study muscular strength in C. elegans. They achieved to obtain results independent of animal behavior and gait in a miniature system consisting of an elastic micropillar forest (Figure 1a and 1b).

The microfluidic system is made of PDMS, and contains bendable micropillars hanging from the microchannel ceiling. The pillars are bent upon the action of the body muscles when C. elegans crawls through the pillar array. Individual pillar bending events can be quantified using a microscope-camera system and image analysis (Figure 1c). The pillar density is designed to create high mechanical resistance to locomotion, therefore maximum exertable force can be measured independent of animal behavior. Here, maximum exertable force corresponds to the peak force exerted by human quadriceps muscle in a standardized knee extension resistance test.

Figure 1. (a) Image of the microfluidic device with the pillar forest and the ports. (b) Schematic demonstration of the C. elegans strength measurement apparatus. Inset shows a scanning electron microscope picture of the pillars. (c) A sketch of interaction with a pillar by the worm body. The pillar is bent due to the action of the body muscles (shown in red and green). Image from Rahman et al.

The authors of this study explain that animals produce strong forces in highly resistive areas and demonstrate different locomotion regimes based on the body size relative to gap between pillars. Besides the body size, body configuration and behavioral characteristics can be the sources to the magnitude of the force exerted on the pillars. Thanks to the probabilistic nature of the parameters sourcing of the force exerted, a reproducible algorithm can be defined for quantifying muscle strength. Using this strategy, researchers showed for the first time that locomotion between microfluidic pillars comprises of three regimes: non-resistive (worm contacts with 1-2 pillars and doesn’t adjust body posture), moderately resistive (worm contacts with >2 pillars and minimally adjust body posture), and highly resistive (worm contacts with multiple pillars and body posture adjustment is disabled). When operated at highly-resistive regime, the microfluidic system suppresses the animal behavior. This system allows for (1) discriminating between the muscle strength or weakness levels of individual worms of different ages, (2) determining body length decrease and muscular contraction levels led by levamisole treatment, (3) comparing the muscular strength in the wild and mutant C. elegans types. According to the researchers, the future studies can help us to obtain deeper understanding in molecular and cellular circuits of neuromuscular function as well as dissection of degenerative processes in disuse, aging, and disease.

To download the full article for free* click the link below:

NemaFlex: a microfluidics-based technology for standardized measurement of muscular strength of C. elegans

Mizanur Rahman, Jennifer E. Hewitt, Frank Van-Bussel, Hunter Edwards, Jerzy Blawzdziewicz, Nathaniel J. Szewczyk, Monica Driscolld, and Siva A. Vanapalli

Lab Chip, 2018, Lab on a Chip Recent Hot Articles

DOI: 10.1039/c8lc00103k

About the Webwriter

Burcu Gumuscu is a postdoctoral fellow in Herr Lab at UC Berkeley in the United States. Her research interests include development of microfluidic devices for quantitative analysis of proteins from single-cells, next generation sequencing, compartmentalized organ-on-chip studies, and desalination of water on the microscale.