We are delighted to introduce our latest Lab on a Chip Emerging Investigator, Rebecca Pompano.

Dr. Rebecca Pompano is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Chemistry and Biomedical Engineering at the University of Virginia, and a member of the Beirne B. Carter Center for Immunology Research. She completed a BS in Chemistry at the University of Richmond in 2005, and a PhD in 2011 at the University of Chicago, working in the laboratory of Dr. Rustem Ismagilov. She completed a postdoc in the University of Chicago Department of Surgery, leading a collaboration between Dr. Joel Collier, a tissue engineer, and Dr. Anita Chong, an immunologist. Since 2014, she has been a faculty member at UVA, where her research interests center on developing microfluidic and chemical assays to unravel the complexity of the immune response. She received an Individual Biomedical Research Award from The Hartwell Foundation and the national 2016 Starter Grant Award from the Society of Analytical Chemists of Pittsburgh. Recently, her lab was awarded an NIH R01 to develop hybrids of microfluidics and lymph node tissue to study inflammation. In addition to her research, she is active in advocating for continued funding for education and biomedical research on Capitol Hill.

Dr. Rebecca Pompano is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Chemistry and Biomedical Engineering at the University of Virginia, and a member of the Beirne B. Carter Center for Immunology Research. She completed a BS in Chemistry at the University of Richmond in 2005, and a PhD in 2011 at the University of Chicago, working in the laboratory of Dr. Rustem Ismagilov. She completed a postdoc in the University of Chicago Department of Surgery, leading a collaboration between Dr. Joel Collier, a tissue engineer, and Dr. Anita Chong, an immunologist. Since 2014, she has been a faculty member at UVA, where her research interests center on developing microfluidic and chemical assays to unravel the complexity of the immune response. She received an Individual Biomedical Research Award from The Hartwell Foundation and the national 2016 Starter Grant Award from the Society of Analytical Chemists of Pittsburgh. Recently, her lab was awarded an NIH R01 to develop hybrids of microfluidics and lymph node tissue to study inflammation. In addition to her research, she is active in advocating for continued funding for education and biomedical research on Capitol Hill.

Read her Emerging Investigator Series article “User-defined local stimulation of live tissue through a movable microfluidic port” and find out more about her in the interview below:

Your recent Emerging Investigator Series paper focuses on stimulation of live tissue through a movable microfluidic port. How has your research evolved from your first article to this most recent article?

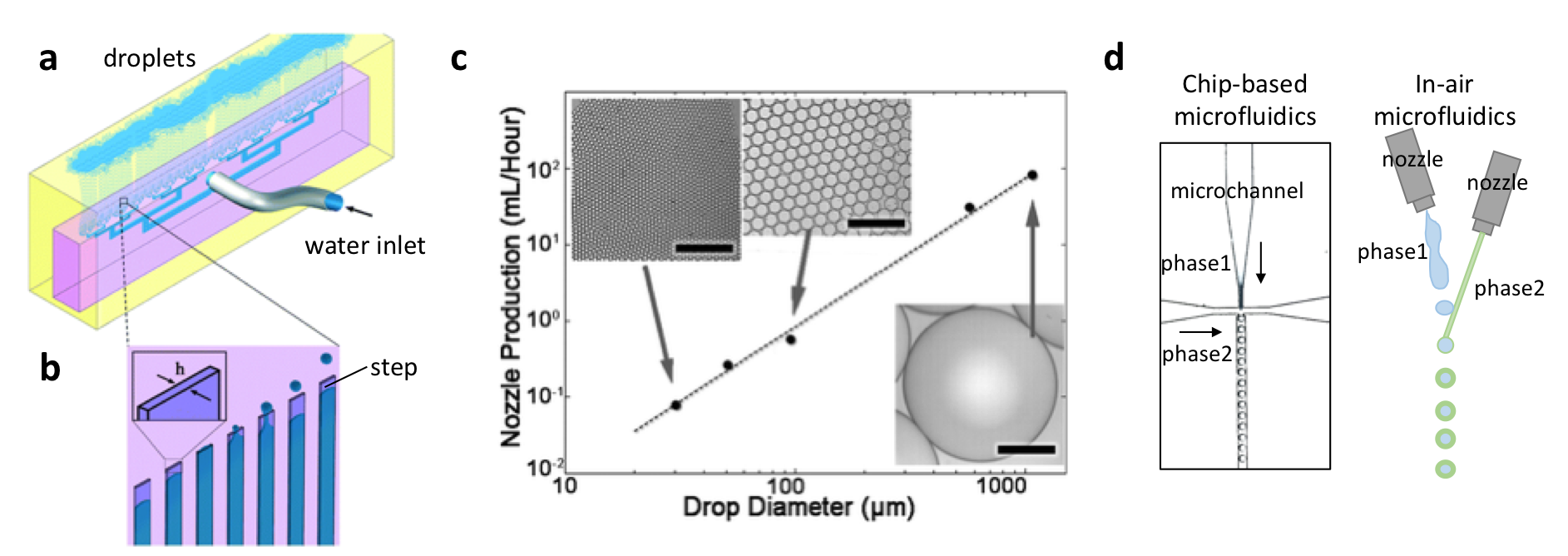

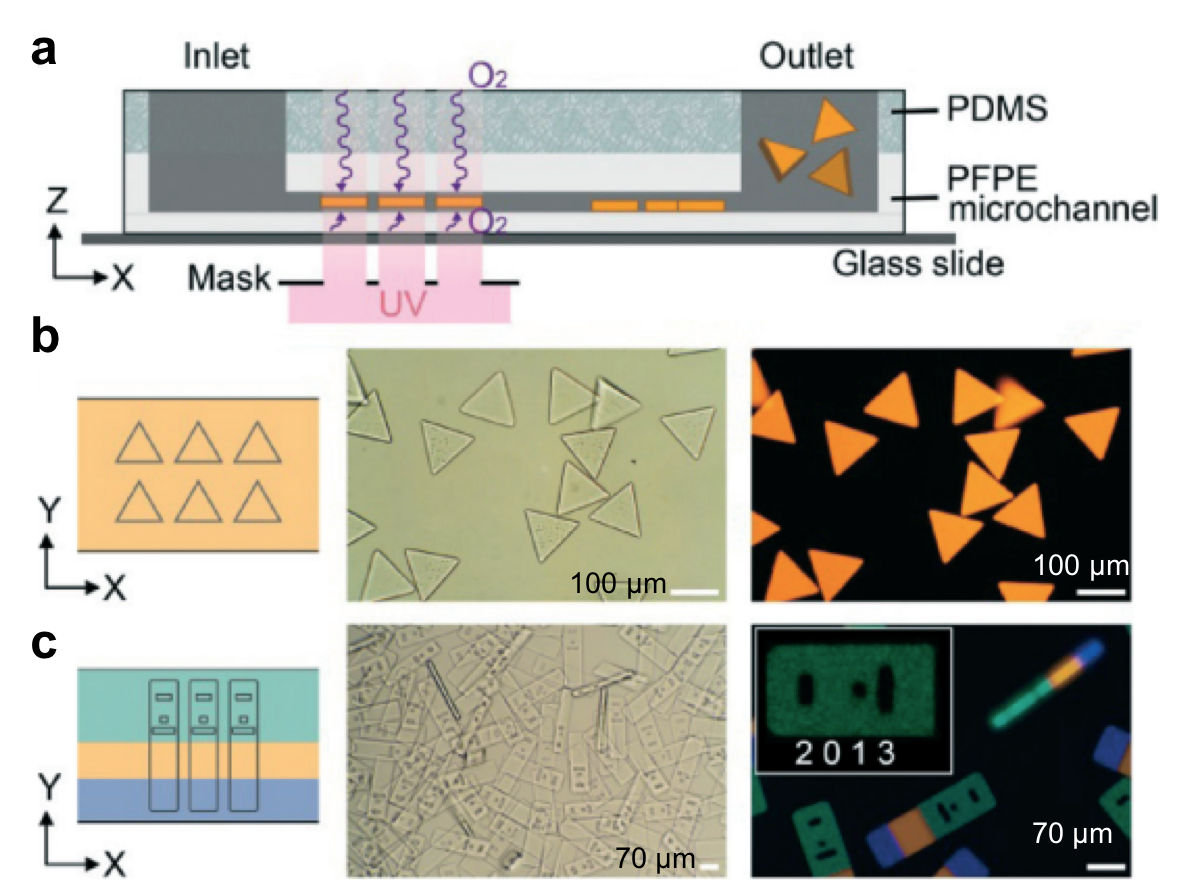

My current research combines some seemingly disparate themes from my prior work. My first article in graduate school used droplet microfluidics to study blood clotting, and I became fascinated with how spatial organization affects the function of complex biological systems. Later, I also worked on the physics of fluid flow in a reconfigurable SlipChip device… and both of these ideas make a comeback in this current paper! Then in my postdoc, I had the fabulous opportunity to work in both a bioengineering lab and an immunology lab, studying the mechanism of action of a new non-inflammatory vaccine. The research in my lab now is really at the intersection of bioanalytical chemistry, bioengineering, and immunology. We develop new tools to study the immune system and how it is organized. This particular paper offers a new technology to pick and choose where to deliver a drug or stimulant to a piece of live tissue, and we demonstrated it for lymph nodes, our favorite immune organ.

What aspect of your work are you most excited about at the moment?

I am very excited about the ideas we are pursuing, specifically that our tools to control and detect how tissue is organized might prove useful for other researchers. As a chemist by training, I’m thrilled to collaborate with creative bioengineers and immunologists like Jennifer Munson (Virginia Tech) and Melanie Rutkowski (U Virginia) to work on inflammatory diseases and tumor immunology. Seeing our chips at work in their labs is very rewarding.

In your opinion, what is the biggest advantage of using local stimulation over global stimulation for measuring tissue responses?

Local stimulation, by which I mean delivering fluid or a drug to one region of tissue, rather than bathing the entire sample in media, gives you the chance to ask unique questions about spatial organization. For example, I envision using this microfluidic technique to determine whether a drug is more effective when delivered to one area of tissue than another, and then developing a nanoparticle that targets just the right region. It can also be used to mimic local biological events, like diffusion of signals from a blood vessel, to determine how inflammation initiates and propagates through live tissue.

What do you find most challenging about your research?

Studying the immune system – its complexity is what I love about it, but it is challenging when the cells and tissue do exactly the opposite of what you expected! This happens over and over when we ask a real biological question. I suppose it shows how much there is still to learn, and why new tools are so desperately needed to predict and control immunity.

In which upcoming conferences or events may our readers meet you?

I’m looking forward to MicroTAS in Taiwan this year. I also bounce around between Pittcon (analytical chemistry), the Society for Biomaterials annual meeting, and the annual AAI Immunology conference. This fall I’ll be attending the BMES annual meeting (Biomedical Engineering Society) for the first time! There is not yet a focused conference for immunoanalysis and immunoengineering, but I’m hoping one will form soon.

How do you spend your spare time?

A few years ago I would have said knitting… I had a great group of friends in graduate school who would get together to knit every week. I still wear those socks and sweaters! Now though, my husband Drew and I spend most of our free time playing together with our 2-year old, Jasper. Sometimes I also go to Drew’s gigs to be a rock star’s spouse instead of a chemistry professor for a while. He’s a bassist in several great bands in Charlottesville (check a few of them out – Pale Blue Dot and 7th Grade Girl Fight).

Which profession would you choose if you were not a scientist?

I almost went into science policy instead of academia. I seriously entertained the idea of working at USAID helping promote vaccines internationally, or working in a think tank to help guide health-related policies. I’m still very passionate about the need for scientists to inform the public and our elected officials about the science underlying issues like health, education, and care of the environment.

Can you share one piece of career-related advice or wisdom with other early career scientists?

A former mentor recommended me the book, Ask For It, by Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever, and it completely changed how I operate. I think many early career scientists could benefit from this book, which is about overcoming self-doubt to ask for what you really need. Although ostensibly written for women, in science I see so many men and women who could achieve something great with just a little confidence booster.