Shannon Faley, Bradly Baer, Matthew Richardson, Taylor Larsen, and Leon M. Bellan*

Vanderbilt University, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Nashville TN, 37235, USA

Why is this useful?

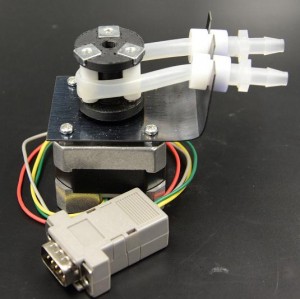

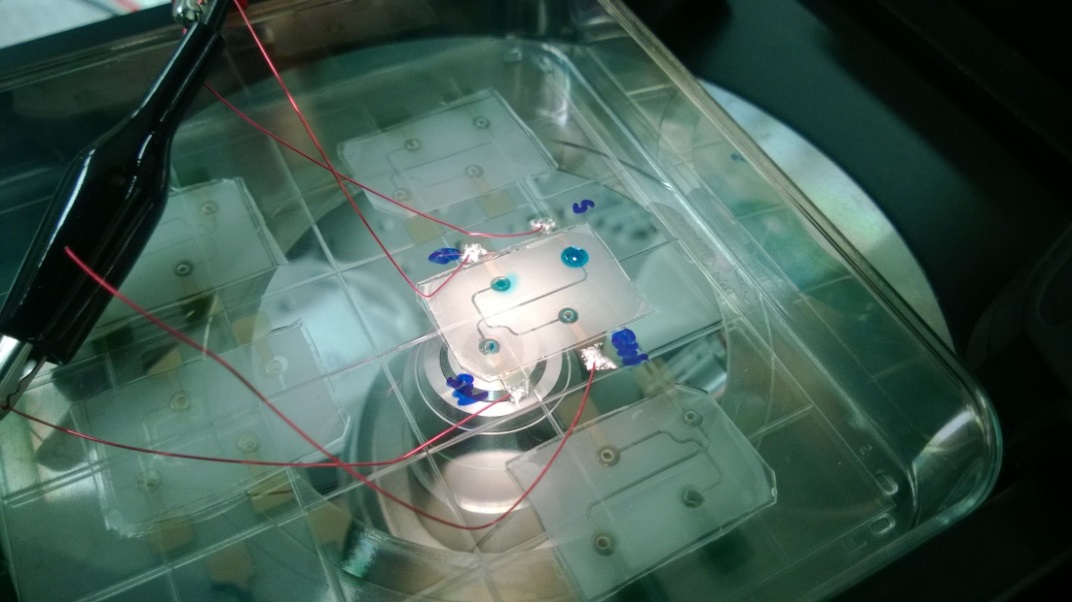

The majority of microfluidic applications require an external pumping mechanism. Multi-channel, individually addressable pumps are expensive, often large, and prone to failure when operated inside cell culture incubators at 95% humidity. The number of experiments that can be run at a given time is limited by the availability and expense of pumps. Perfusing artificial tissue scaffolds containing engineered vasculature requires long-term (days to weeks) continuous flow at low rates. We designed an inexpensive (~$100 for 2 pumps, ~$70 for each additional set of 2 pumps) peristaltic pumping system using an Arduino- controlled stepper motor fitted with a custom 3D-printed pump head and laser-cut mounting bracket. Each pump has a footprint roughly that of the NEMA 17 stepper motor and is easily controlled individually using open source software. Up to 64 motor shields can be stacked for a given Arduino Uno R3, each capable of supporting two stepper motors, and thus has the expansion potential to control 128 pumps in parallel. We have successfully implemented two stacked motor shields driving four independent stepper motors. Flow rate is dependent upon both tubing diameter and step rate. We found flow rates to range between ~50-250 μl/min for 1/16” tubing and ~500-1500 μl/min for 1/4″ tubing. We anticipate that this pump design will likely prove more resilient to incubator humidity compared to standard peristaltic pump powered by DC motors. Since implementation, these pumps have functioned without fail for 3 months (intermittent) under humid conditions. In the event of failure, however, cost of motor replacement is an economical $14.

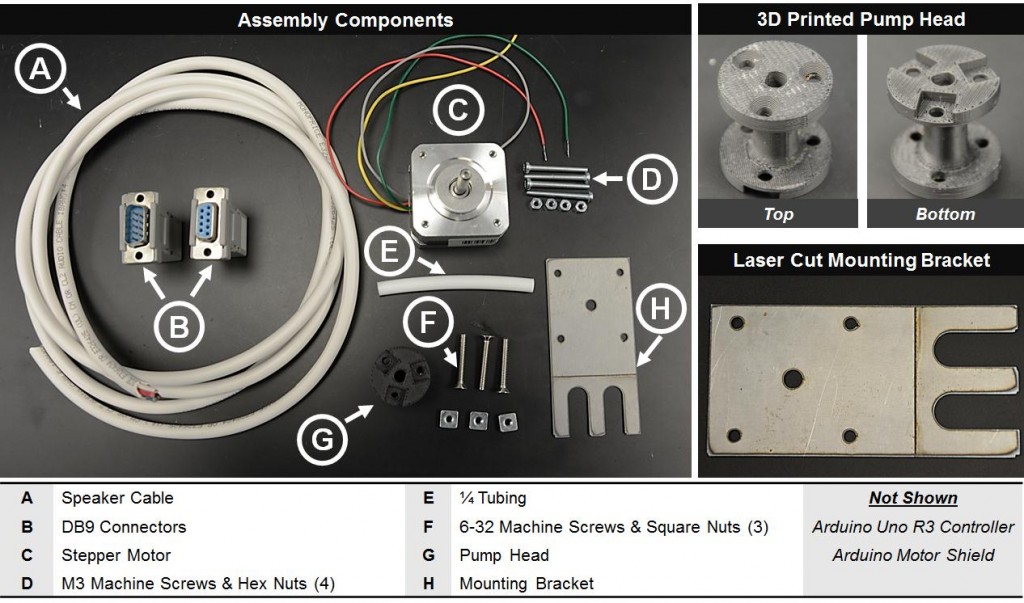

What do I need?

Materials:

- Nema 17 stepper motor ($14, spec, vendor)

- Arduino Uno R3 Controller ($25, spec, vendor)

- Arduino Motor Shield ($20, spec, vendor)

- M3 machine screws (4) & hex bolts (4) ($1, McMaster-Carr)

- DB9 Male & Female Solder Connectors ($9, StarTech)

- 18AWG 4C speaker cable ($10, Monoprice)

- Spring steel

- ABS Filament

- 6-32 machine screws & square nuts (3) ($1, McMaster-Carr)

Equipment:

- 3D printer

- Laser/Metal cutter

- Soldering iron & solder

- Butane torch

What do I do?

Pump head fabrication:

- Using ABS filament, 3D print pump head from file pumphead.crt.9

- Cut three 15 mm (length) sections from rigid ¼” tubing to serve as rollers.

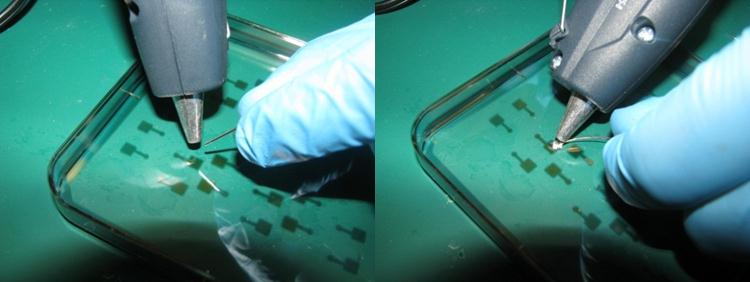

- Use the three 6-32 machine screws and square nuts to assemble the tubing to pump head as shown in Figure 3.

Mounting bracket fabrication:

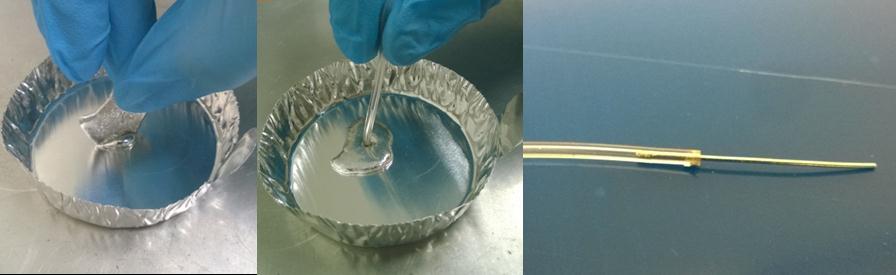

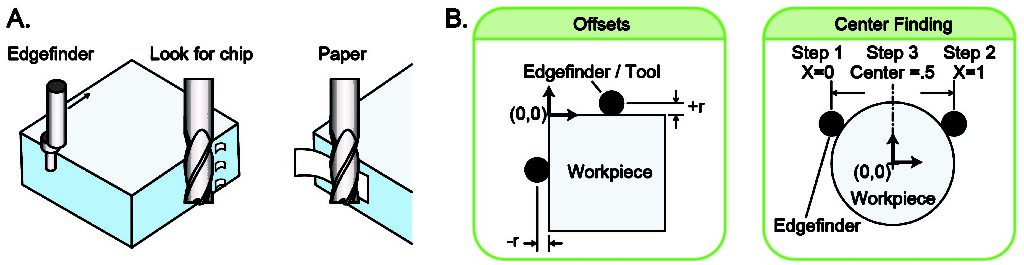

- Using bracket template file (2000 Pump Mount v4) and laser cutting facilities, produce a mounting bracket from spring steel, or other appropriate metal. Note that the score line bisecting the bracket is intended to be cut at a lower power. This line is just a marker to show where to bend the bracket in the following step.

- Using handheld butane torch, heat mounting bracket along score line and bend with pliers. Repeat until mounting bracket forms a right angle (see Figure 1).

Motor Electrical Wiring: (see figure 4 for example orientation)

- Solder motor wires to DB9 Male Connector

- Solder one end of speaker wire to DB9 Female Connector

- Connect opposite end of speaker wire to Arduino Motor shield

Pump Assembly:

- Use M3 machine screws to attach mounting bracket to stepper motor, with corresponding hex nuts as spacers between motor and bracket.

- Press fit pump head onto rotor shaft.

- Connect motor to Arduino using DB9 connectors

Arduino/Motor Shield Assembly:

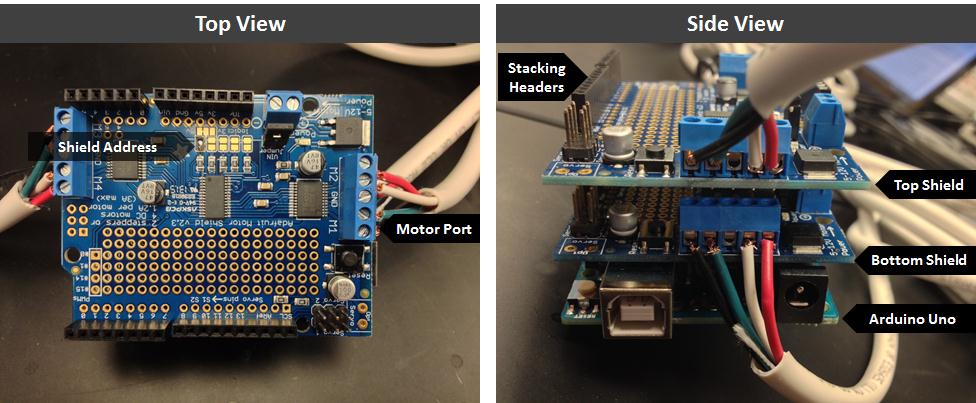

- Follow assembly instructions provided by adafruit.com (https://learn.adafruit.com/adafruit-motor-shield-v2-for-arduino/stacking-shields). See also Figure 5.

Computer Control:

1. See online resources for easy starter code (https://learn.adafruit.com/adafruit-motor-shield-v2-for-arduino/install-software)

2. Load example code to control 2 stacked motor shields running four independent pumps simultaneously. (foursteppers_v2.ino)

3. Start pumping! See video clip for multi-pump demonstration:

Please click here to download the DIY Peristaltic Pump Files