I heard someone ask recently: Has the same water been going around since the dinosaurs peed into it? Intriguing, especially when we think about it in the context of water reuse. Climate change is causing more extreme droughts and floods. As our growing population struggles for equitable allocation and access to limited freshwater resources, we are faced today with an urgent need to diversify our water portfolio.

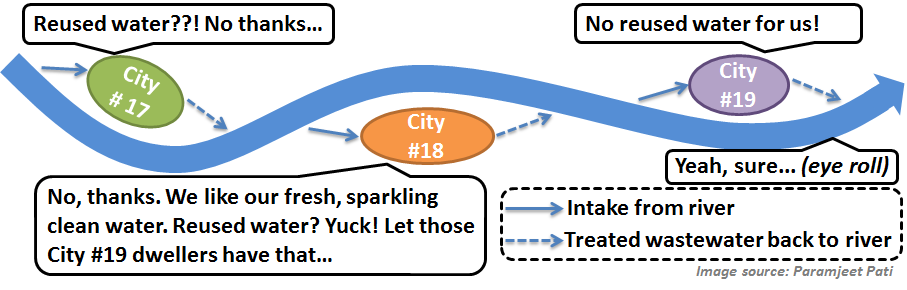

Policy innovations for recycled water – The long view. Effective tackling of water security challenges demands policy innovations. We wholeheartedly endorse policies and technological innovations related to rainwater harvesting, fog catching or decentralized solar-enabled water purification systems (e.g., the Watercone). But using recycled water seems yucky, and efforts to encourage the use of recycled water have received some strong pushback in the past.

The recent droughts in California, however, have resuscitated the discussions about water recycling in the United States. But how successfully do water recycling policies survive the ebbs and flows of environmental stresses, political will, and public memory? Dr. John C. Radcliffe’s recent article gives new insight into this question. The article outlines the successes and shortcomings of Australia’s water recycling over the last two decades, when the prolonged “Millennium Drought” in the 2000s made it necessary for Australia to adopt alternative strategies for water security, and to develop new policies for potable uses of recycled water. Things looked promising for Australia’s long-term water sustainability… but then the droughts ended.

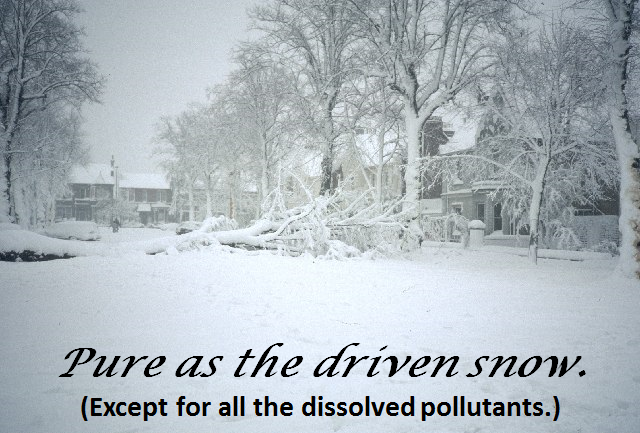

Complacency + the Yuck factor = Terrible, no-good, very bad self-inflicted water crisis. Our resolve to address water sustainability issues and to implement long-term solutions is often tested – ironically – when the threat of water scarcity temporarily fades. As Radcliffe notes, “The end of the drought in eastern Australia has distanced community, industry and government policy focus from strengthening the security of water supply (at almost any cost) to one of pursuing economic efficiency and containing consumers’ water charges and prices.” And the Yuck factor about toilet-to-tap policies doesn’t help.

Blue Gold slipping through our fingers. The poignant opening lines of an Urdu ghazal from yesteryears croon: Duniya jise kehte hain / jaadoo ka khilona hai / Mil jae toh mitti hai / kho jae toh sona hai. Meaning: This world is magical. Here, when we are fortunate to have something, we treat it like dirt (mitti). But as it begins to slip away, it becomes precious like gold (sona). Opportunities to successfully meet our water challenges are shrinking. That glass of water sitting on the toilet seat on the right has been rightly called Blue Gold. And it is slipping away.

Today, while reassessing our water policies while threats to our water security loom in the horizon, let us not forget the lessons that hindsight has to offer.

You can access the full paper for free* using the link below:

Water recycling in Australia – during and after the drought

John C. Radcliffe

Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol., 2015,1, 554-562

DOI: 10.1039/C5EW00048C

————

About the webwriter

Paramjeet Pati is a PhD Candidate at the Virginia Tech Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology (@VTSuN).

You can find more articles by him in the VTSuN blog, where he writes using the name coffeemug.

————

*Access is free through a registered RSC account – click here to register