The purity of water can mean different things to different people. When I call a glass of water pure, am I saying that it’s safe to drink, or clean enough to be labeled as “research-grade”, or do I mean that it has two molecules of hydrogen for every molecule of oxygen and absolutely nothing else? And where can we find the purest, cleanest water in nature?

Image adapted from Wikipedia

It ain’t pure if it’s natural. It ain’t natural if it’s pure. As rain and snow make their way to the earth, they dissolve particles, minerals and gases. Once on the ground as surface water from rain and snowmelt, the water continues to gather dissolved and suspended materials (including microorganisms), as it flows over the soil and the rocks. Rainwater and snow also contain many pollutants and may not be appropriate for drinking without treatment. So, the next time someone tries to sell you a bottle of “pure natural water”, ask where that pure water came from, because, as Machell et al. say in a recent paper, “Pure water does not exist in nature…”.

If it ain’t pure, is it safe? Indeed this is a key question that links drinking water with public health issues. Very few drinking water quality parameters require legal compliance. The Drinking Water Directive in Europe and the Safe Drinking Water Act in the United States are notable exceptions. But most drinking water quality parameters serve merely as guidelines, rather than specific requirements that can be enforced by law.

Due to increasing stresses on our water infrastructure, we are now forced to look for alternative sources of water (such as wastewater reuse, rainwater harvesting and dual distribution systems for potable and non-potable uses). So, a clear understanding of purity becomes even more important when these alternative sources are used to provide fit-for-purpose or safe-to-drink water.

Image adapted from Wikipedia

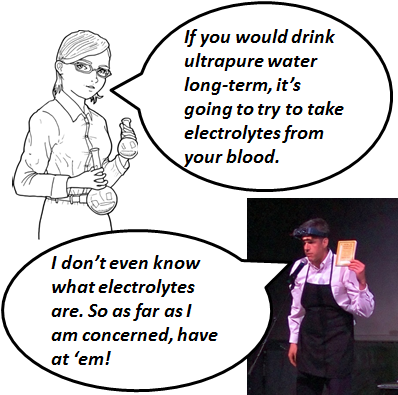

“If I find the world’s cleanest, purest water, I can make the world’s tastiest ice.”, said David Rees in an episode of Going Deep (National Geographic). But he was disappointed after tasting ultrapure water – i.e., water devoid of any impurity. (Perhaps he was also disappointed that he was not allowed do a keg stand, and had to drink the water from a flask.)

In fact, ultrapure water is quite expensive and is an aggressive solvent used semiconductor industry for cleaning wafers – definitely not meant for making the world’s tastiest ice. Rees succinctly summed up the issue: “Don’t overpurify your water – minerals and salts add character.”

An old saying goes: “Water which is too pure has no fish.” Today, we need a more nuanced understanding about water purity to assess the tradeoffs between the cost of treating water and acceptable levels treatment for providing safe drinking water. Indeed, as Machell et al. say, “Water purity is a vague term… Safe water is economical and attainable, whereas pure water is not.”

How does this idea of water purity govern environmental monitoring and risk assessment? Find out by reading the full paper for free* using the link below:

Drinking water purity – a UK perspective

John Machell, Kevin Prior, Richard Allan and John M. Andresen

Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol., 2015,1, 268-271

DOI: 10.1039/C5EW90006A, Forum

————

About the webwriter

Paramjeet Pati is a PhD Candidate at the Virginia Tech Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology (@VTSuN).

You can find more articles by him in the VTSuN blog, where he writes using the name coffeemug.

————

*Access is free through a registered RSC account.