The function of tissues degrade during the course of human life, whether the cause is genetics, accidents, or wear and tear. Frequently experienced medical conditions associated with aging include blocked arteries, cataracts, and arthritis. The former two can be thoroughly treated via surgeries, but arthritis remains a bane to millions of sufferers because its treatment is rather palliative than intensive.

Let’s take the example of rheumatoid arthritis. It occurs when macrophage cells (a main component of the immune system) attack to the membrane (synovium) that surrounds the joints as a result of an auto-immune response. The damaged synovium thickens significantly, its anatomy undergoes striking changes such as metabolic activation of synoviocytes and continuous mass of cells invading into the cartilage and bone. If unchecked this inflammation can destroy the cartilage and the bone within the joint. What does this mean for the patients? A relatively short answer is painful knees, reduced physical activities, continuous uptake of anti-inflammatory medication, and painkillers. A cure does not yet loom on the horizon, but new tools to model rheumatoid arthritis could definitely make it easier to predict the onset of the disorder.

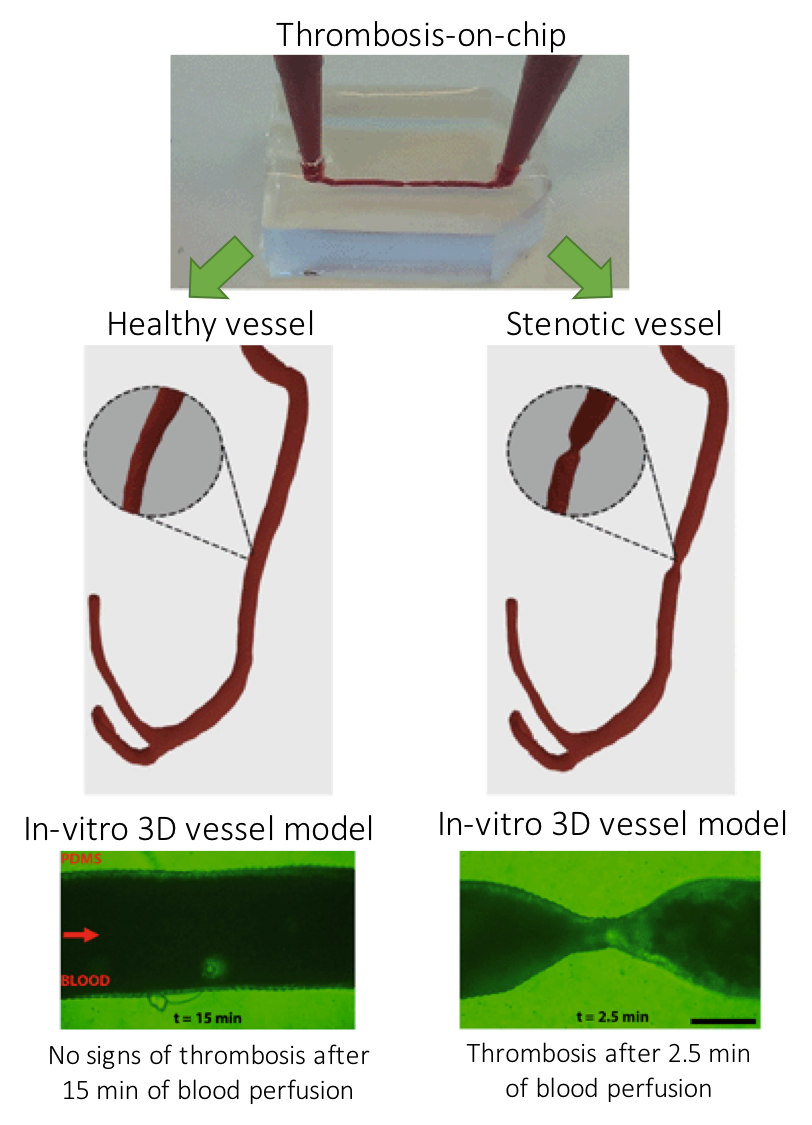

Peter Ertl and his colleagues at Vienna University of Technology, Austria, decided to tackle this problem in the article they recently published in Lab on a Chip. They researched the mechanisms governing the destructive inflammatory reaction in rheumatoid arthritis by designing a first-ever 3D synovium-on-chip tool, which can monitor the onset and progression of the tissue responses. The researchers were focused on monitoring the behavior of the inflated fibroblast-like synoviocytes, which makes the synovium membrane thicker. They used tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) to trigger synoviocytes to demonstrate inflammation response. The chips contained circular microchambers, where surface coatings are applied and Matrigel is filled for obtaining 3D organoids. Different hydrogel types were also examined to observe cell response. For the monitoring, the researchers used collimated laser beams, and the scattered light was collected using embedded organic photodiodes. This powerful optical measurement setup allowed for adjusting the detection range (50 nm to 10 µm) and sensitivity to any tissue construct (Figure 1). The researchers implemented a PDMS waveguide structure to the optical measurement setup to turn the light scattering measurements into reproducible ones. The measurement setup also enabled continuous monitoring of hydrogel polymerization, which was also controlled in this work since the polymerization time influences hydrogel stiffness, which in turn affects the fate of cell behavior. A typical measurement took four days, where the researchers obtained cultures accurately mimicking in-vivo rheumatoid arthritis conditions. A diseased phenotype becomes distinguishable within 2-3 days in the organ-on-chip platform, as this takes at least 14 days in conventional cell culture platforms. The developed tool can very well serve as a new modeling system for inflammatory arthritis and joint-related disease models.

Figure 1. Overview of the synovium-on-a-chip system with integrated time-resolved light scatter biosensing.

To download the full article for free* click the link below:

Mario Rothbauer, Gregor Höll, Christoph Eilenberger, Sebastian R. A. Kratz, Bilal Farooq, Patrick Schuller, Isabel Olmos Calvo, Ruth A. Byrne, Brigitte Meyer, Birgit Niederreiter, Seta Küpcü, Florian Sevelda, Johannes Holinka, Oliver Hayden, Sandro F. Tedde, Hans P. Kiener and Peter Ertl, Lab Chip, 2020, Lab on a Chip Hot Articles

DOI: 10.1039/c9lc01097a

Burcu Gumuscu is an assistant professor in BioInterface Science Group at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. She strives for the development, fabrication, and application of smart biomaterials to realize high-precision processing in high-throughput microfluidic settings. She specifically focuses on the design and development of lab-on-a-chip devices containing hydrogels for diversified life sciences applications. She is also interested in combining data-mining and machine learning techniques with hypothesis-driven experimental research for future research.