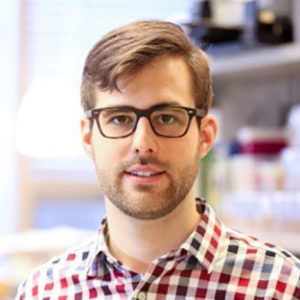

Dr. Scott Tsai is an Associate Professor in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at Ryerson University, and an Affiliate Scientist at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital. He obtained his BASc degree (2007) in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Toronto, and his SM (2009) and PhD (2012) degrees in Engineering Sciences from Harvard University. After a brief NSERC Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Toronto, Dr. Tsai joined Ryerson University at the end of 2012. He leads the Laboratory of Fields, Flows, and Interfaces (LoFFI), which is currently developing innovative microfluidic approaches to generate and use water-in-water droplets and microbubbles in a variety of biomedical applications. Dr. Tsai is a recipient of the United States’ Fulbright Visiting Research Chair Award (2018), Ontario’s Early Career Researcher Award (2016), Canadian Society for Mechanical Engineering’s I. W. Smith Award (2015), and Ryerson University’s Deans’ Teaching Award (2015).

Dr. Scott Tsai is an Associate Professor in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at Ryerson University, and an Affiliate Scientist at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital. He obtained his BASc degree (2007) in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Toronto, and his SM (2009) and PhD (2012) degrees in Engineering Sciences from Harvard University. After a brief NSERC Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Toronto, Dr. Tsai joined Ryerson University at the end of 2012. He leads the Laboratory of Fields, Flows, and Interfaces (LoFFI), which is currently developing innovative microfluidic approaches to generate and use water-in-water droplets and microbubbles in a variety of biomedical applications. Dr. Tsai is a recipient of the United States’ Fulbright Visiting Research Chair Award (2018), Ontario’s Early Career Researcher Award (2016), Canadian Society for Mechanical Engineering’s I. W. Smith Award (2015), and Ryerson University’s Deans’ Teaching Award (2015).

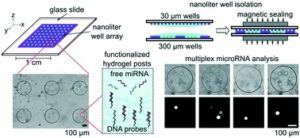

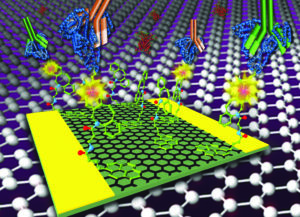

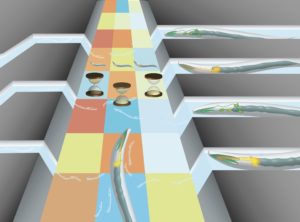

Read Dr. Tsai’s Emerging Investigator Series article “Microfluidic diamagnetic water-in-water droplets: a biocompatible cell encapsulation and manipulation platform” and find out more about him in the interview below:

Your recent Emerging Investigator Series paper focuses on microfluidic diamagnetic water-in-water droplets. How has your research evolved from your first article to this most recent article

My group’s research is contributing to the exciting and emerging theme of all-aqueous and biocompatible water-in-water droplet microfluidics, which was started just a few years ago. Following the pioneering work of others, such as Anderson Shum (University of Hong Kong), we demonstrated that pulsating inlet pressures could be used to break-up all-aqueous threads into water-in-water droplets (Moon et al., Lab on a Chip, 2015). We subsequently simplified the approach by using weak hydrostatic pressure to passively create the water-in-water droplets (Moon et al., Analytical Chemistry, 2016), which enabled other applications, such as cellular encapsulation and release (Moon et al., Lab on a Chip, 2016), Pickering-style stabilization (Abbasi et al., Langmuir, 2018), and diamagnetic manipulation, as described in this paper. I am really excited to see what other tools emerge in the coming years that leverage water-in-water droplet microfluidics.

What aspect of your work are you most excited about at the moment?

I think right now, we as a community are still in the phase of developing the functionality and performance of water-in-water droplet microfluidics platforms. However, I have not seen many papers that leverage the unique characteristics of water-in-water droplets, which are based in aqueous two phase systems (ATPS). For example, ATPS fluids can selectively partition molecules and cells into or out of the droplet phase. I am most excited to see what we and other researchers can create that exploits unique features such as this.

In your opinion, what do you think is the future of droplet encapsulation technologies for single cell analysis?

Predicting the future is always difficult, but I would say that at some point there will start to be some kind of standardization of encapsulation technologies, so that the entire field can move further into single cell analysis applications.

What do you find most challenging about your research?

I find that the most challenging aspect is related to selecting the right problems to work on. Water-in-water droplet microfluidics is emerging and there are many possibilities for research in this area. However, we have limited resources like time and funding, so we have to be selective about which problems to work on, and try to pick the ones that we think will have the greatest impact on advancing the field.

In which upcoming conferences or events may our readers meet you?

I always enjoy learning more about fluid mechanics at the American Physics Society’s Division of Fluid Dynamics (APS-DFD) meeting. I am also a huge fan of the Ontario on a Chip symposium, which was sponsored by Lab on a Chip this year. I was the co-host with Edmond Young and Milicia Radisic (both from the University of Toronto) of Ontario on a Chip for a few years, and my entire group attends the symposium every year. The keynote talks by international leaders in our field draws many attendees, but I am also always amazed by the quality of the student presentations.

How do you spend your spare time?

These days, my spare time is mostly spent with my young family—my wife Edlyn, and my two daughters, Abigail (4) and Chloe (1). I also do some volunteer work for my church. Additionally, as kind of an avid cyclist, I enjoy mountain biking on weekends, and road biking for my commute to work, and for charity rides for example Ride for Heart. Interestingly, I also bike commute sometimes with my Ontario on a Chip co-host, and LOC Emerging Investigator Edmond Young – so perhaps cycling contributes to one’s ability to be a good investigator!

Which profession would you choose if you were not a scientist?

This seems to change at various points in my life. (If you had asked me this question when I was a teenager, I would have probably said that I wanted to be a professional basketball player.) Right now, I think if I was not a scientist I would probably be a bicycle mechanic. Indeed, if I ever retire from science, I might actually attempt to get a job as a mechanic at my local bike shop.

Can you share one piece of career-related advice or wisdom with other early career scientists?

Find a mentor that is well-established, willing to help you, and understands the intricacies of academia, funding, and other aspects of science careers. I was fortunate to receive this kind of mentorship from one of my collaborators from the start of my independent research career. I regard this mentorship as probably the most important factor that has helped me advance in my career.